#365) “The Double Helix:” James Watson Was As Savvy As George Lucas

August 12th, 2014

Whether he ever knew of Joseph Campbell‘s work or not, when James Watson wrote “The Double Helix,” he was as tapped in to the template of the Hero’s Journey as George Lucas when he created “Star Wars.” In this guest essay, my Benshi editor of the past year, Steph Yin, breaks down “The Double Helix,” using both the Logline Maker of our Connection Storymaker app, as well as the Story Cycle found in books like “Winning the Story Wars.” I read “The Double Helix” as an undergraduate, a long time ago, yet it still sticks with me. There’s a reason for that, as Steph demonstrates here.

THE DOUBLE HELIX. This classic tale of scientific discovery, like so many other timeless stories, fits snugly into the Hero’s Journey.

THE MOLECULAR BIOLOGIST’S JOURNEY

Steph Yin graduated from Brown University last year and has been working part-time with me since then, running the Benshi and helping with my social media efforts. She’s a superstar who is headed to NYU in a couple weeks to begin working on her master’s degree in science journalism with this year’s Pulitzer Prize winner Dan Fagin. In January she helped me run the version of our Connection Storymaker Workshop at the SICB meeting in Austin, which gave us a chance to have in-depth conversations about the elements in our Connection Storymaker app.

Out of those chats came the realization that James Watson’s “The Double Helix” is a classic tale of a singular protagonist on a journey in search of a golden chalice in which he overcomes many obstacles to eventually succeed. More importantly, it’s one of the best-told stories from the world of science ever. We both wondered how closely Watson’s tale matches the template of the Hero’s Journey as originally described by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 foundational work, “Hero with a Thousand Faces.” Turns out it’s amazingly close, in addition to embodying a number of other great aspects of effective broad communication. The following is Steph’s analysis of “The Double Helix” from this perspective.

COMPARISON: THE ABT VS. THE LOGLINE MAKER

When Randy suggested that I read “The Double Helix” and investigate his suspicion that the story fit the classic Hero’s Journey model, I took it as an opportunity to grow two flowers with one seed. I had been meaning to read “The Double Helix” for ages, and had also just successfully used the logline maker in a serious way for the first time.

Though I had been working with Randy for nearly half a year, I could never fully appreciate the logline maker; some part of it always felt a bit contrived. After this recent success, I was hungry to apply the Hero’s Journey in different ways and flesh out my understanding of its potential.

Up until that point, the Storymaker’s logline template, based on the Hero’s Journey, had met with varying levels of success in Randy’s Connection Storymaker Workshops. While people intuitively grasped the “ABT” (and, but, therefore) storytelling template, they had a little more trouble trusting the Hero’s Journey template.

Randy believed this happened in part because once people generally settled on the story they wanted to tell, they were reluctant to modify it. While most stories by nature fit the ABT model easily, the Hero’s Journey takes a little more finagling. So when asked to use it as a template, people tend to find the exercise stifling and a bit forced.

The ABT is a practical and versatile tool. It can tell the story of an environmental hero who saves a watershed, explain how subatomic particles collide, or interpret a Mars rover discovery. The logline is much more human-centric—using more theatrical terms like “protagonist” and “ordinary world.” As a result it can seem not just distant, but downright flaky, even, to research scientists. Randy and I decided that for scientists to grasp the potential relevance of the logline, we needed a strong example of how a story of scientific research could fit within its framework (cue “The Double Helix!”).

BREAKING DOWN “THE DOUBLE HELIX”

Reading “The Double Helix,” I was struck by the candid nature of Watson’s writing. He became immediately familiar to me, and this, in turn, made reading the book much more enjoyable—as if I were reading letters from a friend. Watson has all the trappings of a flawed protagonist: he is young, foolhardy, searching for fast shortcuts to fame and seduced by the world of the educated, European socialites around him. His flaws set him up to undergo the Hero’s Journey.

Below is a summary of this journey, using the language of the Connection Storymaker logline:

In an ordinary world, a flawed protagonist: In an ordinary world, James Watson is a young scientist at the University of Chicago, primarily interested in studying birds, impatient for fame and looking for career shortcuts (in particular, avoiding taking any advanced chemistry, physics or math courses).

Feeling unfulfilled by ornithology, he becomes curious about how genes work. He starts grad school at Indiana University, advised by microbiologist Salvador Luria. At this point, he is interested in studying DNA but still hoping to avoid learning any deep chemistry.

A catalytic event happens: He gets his life upended when, in the spring of 1951, he goes to a conference in Naples and hears a talk on X-ray diffraction of DNA by Maurice Wilkins, a physicist and molecular biologist at King’s College. Around the same time, Watson realizes that these conferences were as much a gateway into a fashionable social scene as they were an entry into academia. He writes, “an important truth was slowly entering my head: a scientist’s life might be interesting socially as well as intellectually.”

After taking stock, the hero commits to action: After taking stock, Watson becomes determined to learn chemistry and solve the structure of DNA. He decides to go to the University of Cambridge to learn X-ray crystallography. There, he meets and bonds with Francis Crick, who is also interested in DNA. Watson writes, “From my first day in the lab I knew I would not leave Cambridge for a long time. Departing would be idiocy, for I had immediately discovered the fun of talking to Francis Crick. Finding someone in Max [Perutz]’s lab who knew that DNA was more important than proteins was real luck… Our lunch conversations quickly centered on how genes were put together.”

Together, Watson and Crick commit to finding the structure of DNA using a combination of X-ray photography and model building, a method that had recently been used by the biochemist Linus Pauling to understand the structure of proteins.“Within a few days after my arrival, we knew what to do: imitate Linus Pauling and beat him at his own game,” writes Watson. “Now, with me around the lab always wanting to talk about genes, Francis no longer kept his thoughts about DNA in a back recess of his brain… No one should mind if, by spending only a few hours a week thinking about DNA, he helped me solve a smashingly important problem.”

The stakes get raised: After a while, Watson and Crick think they have stumbled across a breakthrough. They believe DNA is a three-chain helix with phosphate groups held together by Mg2+ ions. However, when Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin (who were studying DNA at the same time) visit Cambridge at Watson and Crick’s request, they quickly find holes in this three-chain theory. Their idea thoroughly shot down, Watson and Crick are discredited, and their superiors order them to stop spending their time on DNA. “By this time neither of us really wanted to look at our model. All its glamor vanished, and the crudely improvised phosphorus atoms gave no hint that they would ever neatly fit into something of value,” writes Watson. “… the decision was thus passed on to Max that Francis and I must give up DNA.”

The hero must learn the lesson, to stop the antagonist and achieve the goal: In order to find the structure of DNA before his competitors (Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, Linus Pauling), Watson must learn to take his time, cultivate a deeper learning of chemistry and mathematics and resist his temptations to take shortcuts or rush to conclusions. For a while, Watson and Crick do their DNA research on the down-low while making progress on their primary research (Watson focused on the structure of tobacco mosaic virus).

During this time, Watson devotes a great amount of time to learning chemistry—combing through scholarly journals and seminal books on the topic. “I used the dark and chilly days to learn more theoretical chemistry or to leaf through journals, hoping that possibly there existed a forgotten clue to DNA,” he writes. “The book I poked open the most was Francis’ copy of ‘The Nature of the Chemical Bond.’ Increasingly often, when Francis needed to look up a crucial bond length, it would turn up on the quarter bench of lab space that John [Kendrew] had given to me for experimental work.” Watson hones his X-ray photography skills, thinks about DNA late into his evenings and continually checks with reference books and colleagues to make sure his chemistry is correct.

By the time he and Crick believe again that they have cracked DNA’s structure (which, of course, this time they had), they are vigilant about checking their assumptions and obtaining exact coordinates before spilling the news, having learned from their earlier fiasco with Wilkins and Franklin. “Keeping King’s in the dark made sense until exact coordinates had been obtained for all the atoms. It was all too easy to fudge a successful series of atomic contacts so that, while each looked almost acceptable, the whole collection was energetically impossible,” writes Watson. “…Thus the next several days were to be spent using a plumb line and a measuring stick to obtain the relative positions of all atoms in a single nucleotide.”

By the end of the book, Watson and Crick have successfully predicted the structure of DNA, and it seems Watson has matured both as a scientist (in his deeper grasp on chemistry and math, as well as in his patience and restraint) and person (who is perhaps no longer as taken with instant fame and the charms of the social elite).

He ends the book in Paris, on a trip with his sister. In the last sentences of “The Double Helix,” he writes, “… now I was alone, looking at the long-haired girls near St. Germain des Prés and knowing they were not for me. I was twenty-five and too old to be unusual.” On that note, our hero turned the page toward a new journey.

#364) Is “Damnation” the Best Environmental Documentary Ever?

August 11th, 2014

First off, I don’t think that’s saying much. The vast majority of environmental documentaries tend to be devoid of story, humorless, preachy, or so preachy as to be dishonest. “Damnation” has a perspective that captures the past century of development in America, but not in a plodding didactic way. It doesn’t just mention Edward Abbey, it is infused with his spirit. It doesn’t just tell about what existed before the Glen Canyon Dam flooded an incredible archeological resource, it shows you through the footage and personal journey of three people that reaches into your heart. It doesn’t just speak of protest—it documents with moments of hilarity pranksters pulling incredible middle-of-the-night dam graffiti stunts. And it amazingly manages to create a voice that plays to both ends of the demographic spectrum – in touch with twenty-somethings with the rebellious pranks, but also playing to the oldest of nature lovers with its dignity. After viewing it a second time on Friday evening at our screening in Los Angeles hosted by the La Cretz Foundation of UCLA I’m even more impressed. I’m sure the odds on it getting an Oscar nomination are long, but I intend to lobby everyone I know in the documentary world. Yes, it is that good.

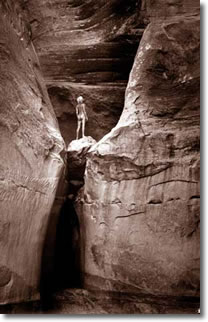

THE RIGHT WAY TO APPRECIATE NATURE. Katie Lee, star of “Damnation,” in 1957 paying homage in her own special way to a tremendous natural resource, before the Glen Canyon Dam desecrated it.

“ED WOULD SHIT HIS PANTS”

If there’s one character in “Damnation” who truly steals the show it’s nonagenarian Katie Lee. You get to see her naked on the Colorado River in the mid-1950’s, taking a rafting trip just before a major section was destroyed by the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam. Her opening line is her reply to the question of whether she’s ever met Floyd Dominy, who was Director of the Bureau of Reclamation in the 60’s and played a significant role in the Glen Canyon project. She replies no, but if she ever did she would, “cut his balls off.” She’s awesome.

In the post-screening panel discussion Matt Stoecker, producer and co-creator of the movie, said she was on a panel discussion for a screening this spring. When asked what Edward Abbey (whom she knew) would have thought of the film she said, “Ed would shit his pants.”

That’s how much spirit the movie has. It’s truly excellent.

Watching it on Friday night at our Los Angeles screening it made me realize the first time you watch a movie you are drawing impressions, trying to decide if you like it. If you do like a movie, then the second time through you get to admire it. Which is what I found myself doing on Friday night.

DIGNITY

If I had to pick one word to describe the movie it would be, “dignified” (yes, despite Katie’s outlandishness). In a world where everyone involved in making issue-oriented movies is trying to pack them full of celebrities (and missing the mark by a mile as “Years of Living Dangerously” did so sadly this past spring) or over-blowing conflict and conspiracy (like a certain fracking film), or unwilling to delve into cultural forces behind destructive behavior (“The Cove” was fun but was an exercise in political correctness when it came to looking into the eyes of a culture that tolerates dolphin slaughter) this movie was simply honest, humble and accurate.

There was no vilification. They let “the bad guys” speak in their own voice, and even put them in a fairly understanding light — showing how they were mostly a product of their times. The country was young, the Depression and World War II did certain things to the psyche of the nation, and a pathway was pursued for the times. No one in the film appeared proud of having destroyed parts of nature. The environment just wasn’t in their thinking. It was an age when wetlands were called swamps and rainforests were jungles. I remember that era. It finally began to change when I was a kid in the 1960’s and the modern environmental movement emerged. For the most part the developers weren’t evil, just myopic.

TIME TO PUSH FOR AN OSCAR NOMINATION

Since making my movie, “Flock of Dodos,” in 2006 for which we never deluded ourselves into thinking about the Oscars I’ve had to witness all sorts of dishonest, massively hyped, deeply polarizing screeds and polemics receive Oscar nominations. “Jesus Camp” and “Gasland” are two that immediately come to mind. Even the Oscar winning “Bowling for Columbine,” wasn’t brilliant storytelling, only loud argumentation.

Surely the world hasn’t devolved to such a state that only the screaming liars receive recognition. This movie has convinced me it is still possible to create an engaging and popular environmental documentary that works (btw, they won the Audience Appreciation Award at South By Southwest Film Festival where they had their premiere). The world needs this film to get all the recognition possible so it can serve as a model in so many ways — not just for environmental filmmaking, but also in educating the world on this entire futuristic trend of dam removal.

We had a great final question in the Q&A on Friday from a young guy from China. He told about the reckless dam construction going on there, then asked if this movie will be shown in China. It needs to be. The Chinese need to see this aspect of the future — that dams are a thing of the past. They need to know that this country, that went dam crazy in the 50’s is no longer building ANY dams, and is instead hard at work removing them with great success.

Let’s all get to work in spreading the word and seeing if it can end up at the Oscars. I’ve never seen a more deserving documentary. Ever.

Sorry. I’m a supporter of climate action, and just raved in my last post about a brilliant environmental documentary, but this thing from the White House is anti-communication. Why would you open with a preachy, dull professor lecturing you? Who exactly is that supposed to be geared towards? Didn’t anyone at the White House hear Daniel Kahneman’s instructions to find a voice that is, “Trusted and Liked.” Who likes being lectured to? And does anyone there understand the power of storytelling? Is this stuff really that difficult? Honest to goodness. Can you say bo-ho-horing.

A HUNKA, HUNKA BURNING BOREDOM.

MAKE IT STOP

I can’t tell you what this video says because I could only take 30 seconds of it. Yes, that is all that today’s audiences give you when it comes to video. Why should they give you more when we know that complete stories can be told in just 5 seconds of video, and Super Bowl commercials tell complex stories in just 30 seconds.

This is really bad. Your average USC undergraduate cinema student could make something far better. Film is a VISUAL medium. The visuals need to say something more than just FIRE. I don’t even know where to start with a critique of this video but I know we get much better work in my videomaking workshops. Sorry to be harsh, but it’s part of the game in filmmaking—you make a film, you get reviews, sometimes they’re not good—just look at the reviews for a movie like “Sex Tape” which I’m sure most people would rather watch than this thing.

Come on, White House, you know how tough communication is these days. You can do much better.

#362) “DamNation”: Excellent Documentary Filmmaking

August 4th, 2014

Last year I scoffed at the biased mess that was “Gasland.” I wish “DamNation” had been out so I could have pointed to it to say this is how you present an issue you have strong opinions about without having the audience feel like they’re being conned. On Friday I’ll be moderating the panel discussion for a Los Angeles screening of “DamNation.” It’s a wonderful film filled with amazing sequences of inspiring protest efforts, beautiful scenery, and a heart-warming if sad jackpot of old movie footage of a trip down the Colorado River that will make you want to cry for the destruction dams have wrought. It’s great and a role model for how to make a solid environmental documentary that addresses a controversial issue in a level headed and dignified way. More movies like it are needed.

DAM IT. The dam poster with the dam photo for the dam movie. It will be screened outdoors this Friday, August 8, at the L.A. Natural History Museum. I’ll be moderating the panel.

DAM PUNS

I bet the filmmakers are tired of reading reviews that try every possible combination of play on the word “dam” — though that’s what they get for doing it with their titled, “DamNation.” Regardless, it’s really a great film and we’re going to have a fun event on Friday when it will be screened outdoors at the L.A. County Natural History Museum.

The post-screening panel discussion will consist of the co-producer Matt Stoecker, Jamie King of California State Parks, and Karina Johnston, Director of Watershed Programs at the Bay Foundation, with me as the moderator.

I really can’t say enough good things about this movie. It’s both nostalgic and contemporary. It’s hip and cool enough to feel like it’s for a younger demographic, yet dignified and even reverential at times to play to the older crowd. It has great visuals, but not at the expense of substance. It also captures the broad sweep of the past century to feel like the voice of the very best of the American environmental movement. Instead of a “you horrible people” tone, it has more of a, “what were we thinking?” approach.

Actually, let me put it simply, I’m willing to bet my good buddy Mark Dowie, author of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated, “Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century,” will love it. His book was kind of a cry in 1995 of, “What happened to the original American environmental spirit?” I think this movie answers that question, saying, “It’s still alive, right here.”

And actually, when you think of the ultimate voice behind it—Yvon Chouinard, the found of Patagonia (who sponsored it)—it all makes sense.

But I do have to make one bitter side comment, which is that this is the sort of movie “Gasland” should have been. Dam removal is potentially just as polarizing and highly charged of a topic as fracking, and there are moments in the movie that tell of human impacts of dams far beyond anything fracking has caused so far. But where “Gasland” was divisive, polarizing and downright stoopid with Josh Fox‘s immediately conspiratorial voiceover (basically “the man is out to get you” voice), this film is humble, honest, respectful and fun.

People squawk at me often, “Well, what is your idea of a good documentary?” This film is my answer, plain and simple. It’s a role model for all aspiring environmental filmmakers. It doesn’t have perfect narrative structure, it has a few minor shortcomings (would have liked a little more explicit addressing of the bottom line on the “jobs vs. environment” divide when it comes to dam removal), but a movie can only do so much in addressing an issue—it’s not the same as a book.

The movie does its job incredibly well. AND … it’s fun!