#226) A Mini-Tutorial at the RNC on Narrative Structure

August 31st, 2012

This is nice, and along the lines of my latest hobby horse — grasping the divide between exposition and storytelling.

HE SHOULD KNOW. John Heilemann, author of the NY Times #1 bestselling book, “Game Change” in 2010 shares a little bit of narrative wisdom before Mitt Romney’s speech.

space

FOR THE THOUSANDTH TIME … DON’T TELL US, SHOW US

John Heilemann is a sharp guy (his bestselling book “Game Change” with Mark Halperin gave rise to the excellent HBO movie that focused on Sarah Palin). He had some savvy advice for Mitt Romney before his speech last night. Here’s what he said:

“We know the difference between illustration and exposition. We had Ann Romney up there the other night and she did things in exposition — she asserted things in bullet point form — “he’s this, he’s that.” But she didn’t give us illustrative stories — anecdotes — things that reveal him. I think this speech has to be like that — it has to be stories about his father, stories about his kids — I think he’s got to go to the places like, talking about Bain — why was he so successful at that, what did he love about Bain, what does he love about his church, what does he love about his family, and tell people about it in a way that makes him not seem like an android any more — that’s his problem — he’s like HAL 2000, he’s not human — he needs to be human.”

This has become one of the major focal points of my communications workshops — getting scientists (in particular) to grasp the difference between exposition (asserting “things in bullet point form” as Heileman puts it) versus storytelling (or “illustration” as he says — same thing). It comes down to the same old DON’T TELL US, SHOW US. Don’t give us a laundry list, tell us a story that illustrates what you’re talking about.

The bottom line of what he’s saying is that Mitt Romney is a scientist and should read the book, “Don’t Be Such a Scientist.” Although, of course, he isn’t a scientist given his ridiculing of sea level rise last night.

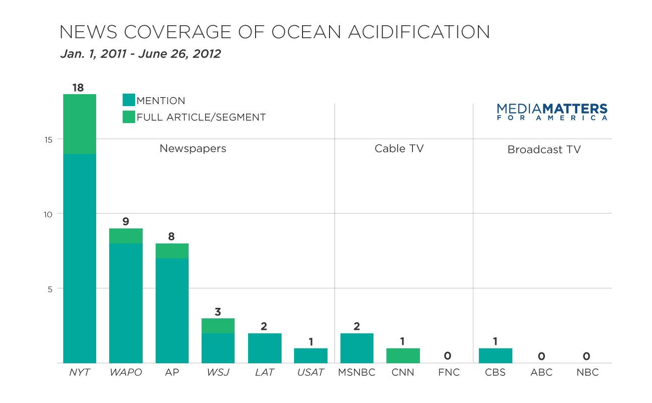

The website Media Matters produced a nice factoid: In the first half of this year, media coverage of the Kardashians was more than 40 times that of the thrilling topic of ocean acidification. Is anyone surprised? Hope not.

DEATH, TAXES AND OCEAN ACIDIFICATION (Name three things you don’t want to hear about).

fin

THE ACID OCEAN REALITY SHOW

A little while back Brett Howell tweeted me this tragi-comic article from Media Matters about the gap in media coverage between the gossip-fodderoids The Kardashians and the not-yet-figured-out-how-to-communicate topic of ocean acidification (big thanks, Brett, sorry it took me a while to get to this, been a busy summer). Turns out there was a 40 times difference for the first half of this year.

The question to ask is, “Does there have to be a gap?” In theory I would say no. But in reality, yep. So you might say, “I guess it’s hopeless,” but I would say, “No, its a question of priorities.” Here’s the basic dilemma …

gone

GOOD, FAST OR CHEAP (PICK TWO)

I’ve run through this before, but this is another case that it applies to. In Hollywood, when you go to your production designer on the set of a movie and say, “I want you to build me the Oval Office,” your production designer will usually reply with, “Okay, good, fast or cheap — pick two. I can make it good and fast, but it’s going to cost you a fortune, I can make it good and cheap, but it’s going to take a few months as I try to recruit friends to donate resources for free, or I can make it for you overnight and for nothing, but you’re gonna have to use your imagination because it ain’t gonna look very good.”

That’s the real world. And the science world, where “fast and cheap” usually rules when it comes to communication (or even slow and cheap!). I know. I was a scientist. Plus I just spoke at a major science meeting (which was a great session, but) where they not only didn’t pay me, they held the meeting in a room with a tiny screen (one third of the size it should have been, using the general rule of thumb they taught us in film school of one inch of screen width per viewer), no speakers for video clips (I had to hold the microphone to my laptop speaker), and no wireless microphone for the presenter. That, to me, is a giant statement of, “We really don’t give a crap if anyone can hear or see you, just show up and do your dog and pony show, whatever.” That’s the science world for you. (and today there’s no excuse given the easy access to examples of how to do it right with all the TED Talks available online, plus this was at a major convention center which could provide bigger screens for starters if anyone asked, but I’m guessing no one even asked — scientists just don’t care about communication)

space

GOOD COMMUNICATION COSTS

That’s all I can tell you. Good, fast or cheap. You get what you pay for. Wanna know why “An Inconvenient Truth,” didn’t have any net effect on the polls (and it didn’t — look at the Gallup Poll — if you think it did, you’re living in the environmental bubble)? They chose fast and cheap. They rushed it into production in the fall of 2005 in panicked response to the summer of 5 hurricanes.

They did not spend $10 million to hire the very best screenwriters in Hollywood to pull a month of all-nighters and come up with a powerfully structured story that mass audiences would be enraptured with and want to tell and retell for decades. No, they rushed a prominent speaker onto a stage to shoot three takes of the Powerpoint presentation he had been giving for a while. No fault of his. He was just trying to help. It was whoever made the decision for cheap and fast. And the science world for not having high enough communication standards to distance themselves immediately from such an effort. Oh, well.

You want to know how to make the topic of ocean acidification compete with the Kardashians? Choose fast, expensive and excellent. The environmental movement is overflowing with funding (just look at last year’s Climate Shift report), and the problem is going to be around for a long time. But if the approach continues to be fast and cheap, don’t expect anyone to take much interest. Until, of course, there’s a major crisis. And then it’s too late. Ho hum.

#224) ESA Session: Crowdsourcerers

August 14th, 2012

It’s fun to hate the masses, but sometimes they leave you amazed. The crowdsource/citizen science phenomenon can be powerful. I heard a few pretty cool examples last week in the session I took part in at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland.

IS THERE REALLY ANY BRAIN POWER IN THIS GROUP OF SCHMUCKS? Hate to admit it, but apparently yes.

space

CALLING ALL NON-EXPERTS

Who knew that average people, combined together, could be so smart and helpful? I saw a few impressive examples last week in the excellent symposium I took part in at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland titled, “Growing Pains: Taking Ecology into the 21st Century.”

First, there was Stephanie Hampton, of the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, who talked about how quickly the various local citizen science groups throughout the Gulf of Mexico last year were able to give a snapshot of the condition of seabirds following the Gulf oil spill. If you think back to 30 years ago when the government, with it’s limited resources, was THE source of such information, you can see how far we’ve come. There was no way the government agencies could have so quickly assessed the state of the seabirds across such a broad region. It was a case of the amateurs being more effective than the experts.

Then Alexandra Swanson of the University of Minnesota told about the rather stunning Serengeti Live project where volunteers get to analyze their photos for them. They have an array of 225 cameras set up in a grid on piece of the Serengeti snapping photos round the clock producing over a million images. Who has the time to analyze so much data? Volunteers, that’s who.

On their website people can volunteer to take on a stack of photos, looking at them for the presence of mammals (elephants, wildebeets, hyenas, etc.) and reporting what they see. They get a little bit of training first, then set to work, helping them plow through the superabundance of images.

Does this sort of “crowd-sourced” effort work? Is it reliable? Is it a bunch of amateur garbage?

maybe

AMATEUR IN, PROFESSIONAL OUT?

What’s happened in recent years, kind of starting with the realization that Wikipedia ends up being as accurate as Encyclopedia Brittanica, is that there is indeed great knowledge among the masses, where the individual limitations are overridden by the staggeringly large sample sizes.

If you want a great and dramatic demonstration of this, read the article in the July 9 issue of The New Yorker about TED conferences. The author uses a speaker on “crowd sourcing” as the central thread of the story. The speaker brings a live ox on stage during his talk, inviting web viewers to text in their guesses on the weight. At the end of the talk they present the average of the 500 guesses, which is 1,792 pounds. The actual weight is 1,795 pounds. Assuming we can believe that craziness (and given the recent feats of disgraced New Yorker writer Jonah Lehrer we should probably be cautious), that’s pretty crazy!

Lastly, I attended a biomedical symposium last year where I met Jamie Heywood, who gave a riveting talk about what has become his life’s work, creating a website called Patients Like Me (here’s his outstanding TED Talk on it). His brother died of Lou Gehrig’s disease (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis), but in the struggle to keep him alive, Jamie created a website for people with the disease which eventually morphed into Patients Like Me which now has over 150,000 people dealing with a wide range of illnesses. On the website the patients create their own personal profiles, sharing huge amounts of details about the medicines they are taking and the outcomes.

The result of the website is an enormous crowdsourced data base that in most cases far surpasses what doctors are capable of. For example, in the case of Multiple Sclerosis, they have over 20,000 patients. Which means if you have the disease and your doctor prescribes a drug, you can ask him how well it’s worked with the dozen or so patients he has who are taking it, or you can go to this website and look at the totaled, up to the minute results of the 20,000 people with MS who are sharing their knowledge on the drug.

The site is so powerful it ends up revealing enormous numbers of errors committed by doctors who simply don’t have the time or interest to keep up on the latest developments with various diseases and drugs. It’s amazing.

Bottom line, it is indeed a new era we have entered into. Or at least that’s what I heard was the finding of a recent poll of one thousand respondents, which means it must be true.

#223) Curiosity: Brilliant Filmmaking from … SCIENTISTS!!!

August 6th, 2012

Two historic things: landing of the Mars probe “Curiosity” and the production of a truly brilliant (especially now that the mission succeeded!) short video by a science institution, JPL.

space

space

DARE MIGHTY THINGS. You betcha. This video would be kinda hard to watch if the mission had failed. But it didn’t. And now it’s a thing of beauty. Complete beauty.

wow

HOW TO COMMUNICATE BRILLIANTLY: EQUALLY GOOD NARRATIVE AND VISUAL ELEMENTS

People ask me for examples of effective communication in the science world. Most stuff is terrible, but this one is truly amazing. It’s from JPL, which is maybe not such a surprise as they have had a long tradition of producing excellent visuals for their projects, but this one is more than just a bunch of cool visuals. It’s as good narratively as it is visually, which is rare.

I like web videos to be about 2 minutes in length. They need to be really good to justify much longer than that. This one is 5 minutes, and feels absolutely perfect.

It speaks for itself. Every element of production is wonderfully coordinated — the pacing of the editing, the graphics, the color palette, the close-ups of the scientists faces — even the sense of urgency in their “performances” — and they must be performances — the filmmakers must have coached them to have gotten such consistency in their tone.

And of course most powerful and effective (and important) of all is the music scoring — building an increasing sense of danger and tension.

Best of all is the finish, which is perfectly executed — like a triple body spin, flawlessly landed at the end of an Olympic gymnastic routine — they describe the last bit of the probe landing, finish on a shot of the rover on the martian surface, then exit with the challenge, “Dare Mighty Things.” Which they truly have. And succeeded.

This is a piece of filmmaking/communication at the same level of achievement as what the scientists have done in landing the probe.

It’s a role model for other science organizations. Judges Score: A perfect “10”. If we ever had a video like this submitted to our S Factor Panels we’d have nothing to say, we would just be humbled.