#279) The Pace Univ. Baja Turtle Doc: The Changing of Minds

May 24th, 2013

This year Andy Revkin’s Pace University course on documentary filmmaking produced their best film yet. It’s an interesting ook at the slowly shifting perception and treatment of sea turtles in Baja, Mexico from food to friend.

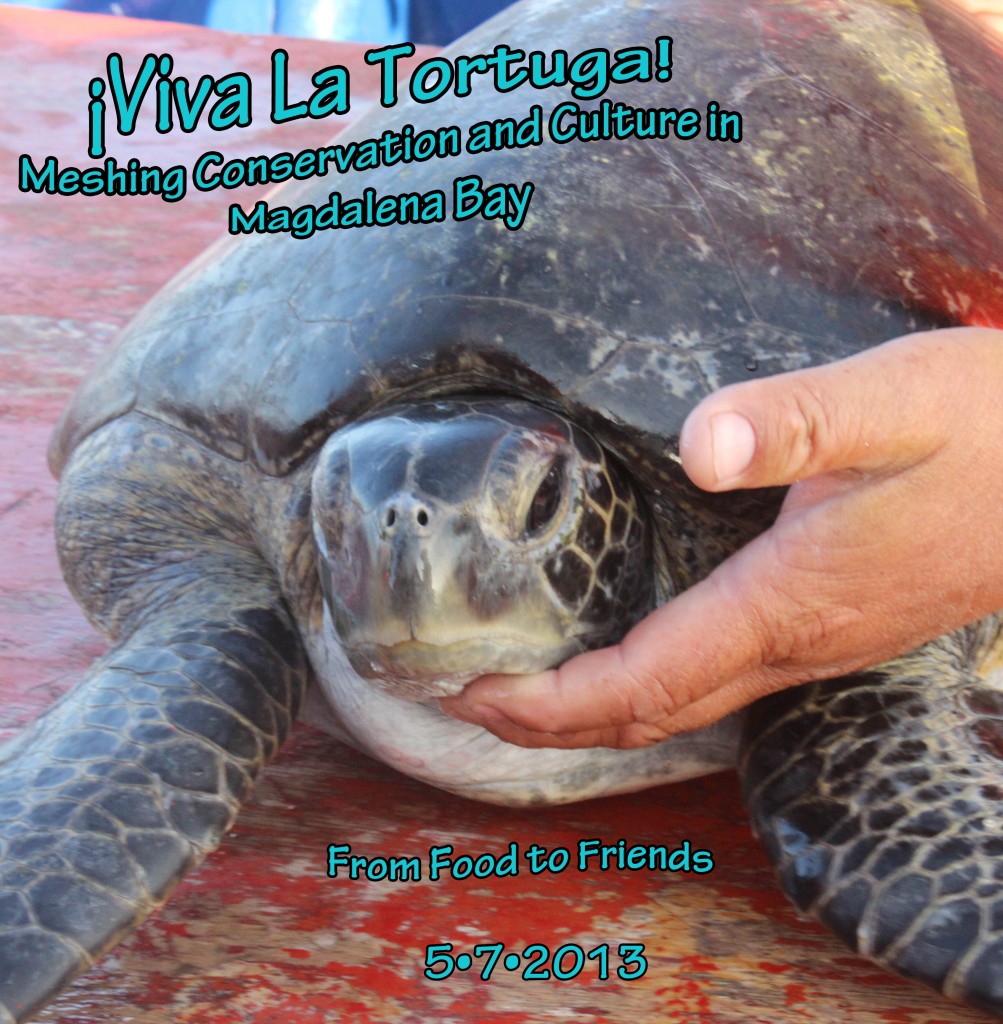

HOW COULD YOU EAT SOMETHING THIS LOVABLE? 12 students, a couple of days of filming in Baja, and presto, a really nice short film showing the complexity of protecting sea turtles in one of their most important regions.

S

TEETERING MINDS

Every spring for the past three years Andy Revkin of the NY Times co-teaches a documentary filmmaking course at Pace University with Maria Luskay where they take the students on a road trip to make a film about nature. Year One was about shrimp farming, Year Two was cork harvesting, now Year Three’s class has produced a very nice 15 minute film about the plight of sea turtles in Magdalena Bay near the bottom of the Baja Penninsula in Mexico.

The film captures the shifting attitudes among the fishing community towards sea turtles. Most of today’s adults were raised to see turtles as food, but are increasingly coming around to accept the need for their protection.

The crew consisted of twelve students, five of whom were graduate students and most of whom had little or no previous film experience. Which makes the film all the more impressive.

“I knew something was wrong,” is the core message of the film, reflected by Dr. Alonso Aguirre of the Smithsonian-Mason Conservation Center. He grew up there being fed sea turtle meat and blood until he finally realized there were better ways to appreciate sea turtles.

Dr. Jay Nichols, long time turtle conservation activist, tells about a major turning point for the local issue when he helped form “Grupo Tortuguero,” starting with about 45 people gathering to discuss the fate of the turtles.

They’ve changed a lot of minds and made a lot of progress, and yet … they say that still, just this spring, there are voices saying enough has been done to protect the turtles. Which serves to illustrate the endless challenge of conservation — i.e. you’re never done.

It’s a great short film and further proof that the power of video as a communication tool is today within the reach of everyone.

#278) TV gooood, not baaaaad

May 15th, 2013

We’ve all been raised with the notion of TV as evil, and yet … not only is crime down in our country and violence on the decline worldwide, but now the Breakthrough Institute folks offer up TV as a significant factor in the decline of birth rates in India and thus famine. With so much non-misery in the world, how is anyone supposed to tell a good story?

THIS is exactly the reason I’ve been such a fan of USC’s Hollywood Health and Society project for the past few years. This is what they work towards — effective messaging through mainstream television shows including soap operas (which are believed to have played a significant part in Brazil’s drastic reduction in fertility rate). Rather than ridiculing the medium, they acknowledge it’s power and reach, and try to work within those constraints. Now here’s an article by Martin Lewis of the Breakthrough Institute that concurs with their approach.

catching

THE NON-HUNGER GAMES

For those of us who were kids in the 1960’s, we grew up with the news of world famine as a routine occurrence. When I was five years old over 15 million people died of starvation in China. Which I guess was why all of us were told at the dinner table to eat our food and not waste anything because of, “All the starving children in China.”

Given that today China practically owns us, that concept now is kinda borderline funny.

Famine used to be so prevalent. It’s yet another shifted baseline — so hard to recall those times, and now the bigger problem in many countries is obesity.

The guys at the Breakthrough Institute, led by Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger, have written yet another excellent essay (I’ve become an increasingly big fan of their writings) which points out, among other things, the non-evil role of television in this transition.

fire

CHANNELING THE BOOB TUBE

Television has always been vilified. I remember my father calling it “the boob tube,” and David Halberstam in his landmark book, “The Powers That Be,” gave the definitive history of it’s decline from the early years of optimism about it’s civic role to the depths of the Beverly Hillbillies and Gilligan’s Island (also known as the golden years to some of us).

But there’s a less obvious and immediate role of television, which is that it both reflects the current state of living as well as potentially sets trends in whatever direction it heads. The good folks at the USC Norman Lear Center for Entertainment Studies realized this more than a decade ago and began a partnership with the Centers of Disease Control to insert their public health messaging into the most widely watched television shows — particularly the narrative fiction shows.

It’s called the Hollywood Health and Society Project, Sandra Buffington has been the Director since its inception, and she gave a great interview to Dave Roberts of Grist in 2011 which he titled (using my father’s favorite term), “How to get the boob tube to tell the truth about climate change.”

tewb

MICHAEL CRICHTON WAS RIGHT

At the core of all this is the media world. Which makes me think of one of the most meaningful experiences I had in the making of my movie, “Sizzle: A Global Warming Comedy,” in 2007. I traded roughly 40 emails with legendary science fiction author and massive climate/environmental skeptic Michael Crichton over the course of four months.

I gave him a little bit of pushback over the nuttiness of his climate skepticism and his bizarre comparisons of discredited Danish statistician Bjorn Lomborg with Galileo (say whuut?). His “State of Fear” book was terrible (he forced me to read it or end the conversation) and he produced a single photo of a meteorological “station” in a wooden box mounted on a telephone pole next to an incinerator can that might cause it problems, which he felt was sufficient evidence to dismiss all of NASA’s climate data for North America.

But the one very valid point he made is that the media world is driven, not by the truth, but by storytelling. He certainly knew what he was saying with this and in the years since I’ve managed to absorb it more deeply. What he said was the truth. If there is such a thing as the truth. And it’s probably the driving dynamic behind this line in Martin Lewis’s fascinating article.

MARTIN LEWIS: “I find it extraordinary that the massive global drop in human fertility has been so little noticed by the media.”

Declining human fertility doesn’t make for a very interesting story. Not nearly as compelling as “population explosion!”. So, indeed, why should the media be interested?

I’ve been going to Groundlings shows for 20 years, yet somehow missed the weekly “Crazy Uncle Joe Show.” Until last week. It truly amazed me. SCIENTISTS: Go see it — just to look at behavior that is polar opposite to yourself. And that’s not a criticism of either group. Just a statement of fascinating fact. Scientists live in a world of carefully controlled precision. Improv actors (especially in a show like this) ride in a car with no driver, and manage to make it work.

Groundlings performer Brian Palermo just after the show. He’s talking to Randy Atkins (of the National Academy of Engineering who was in town for the Broadcom Masters STEM finalists) and actress Dorie Barton. Brian and Dorie are my wonderful and amazingly talented workshop co-instructors.

space

“A PYROTECHNIC SEVEN PERSON DISPLAY OF CLEVERNESS”

A couple weeks ago “The Daily Show,” did a skit about capturing some guy and wanting to subject him to various forms of torture, one of which was, “You will be forced to watch a 90 minute long form improv comedy show.” Oich. That’s a pretty serious threat.

Improv is a technique that spreads the variation when it comes to comedy quality. A lot of it is painfully bad (particularly from actors who are not well trained), but some of it is far better than you could ever get with scripted performance since it has that spark of spontaneity and energy that can’t be faked. The highs can be so high that they justify all the lows. At least when the performers are really good.

When it’s done to the ultimate of it’s ability, it can be, “A pyrotechnic seven person display of cleverness.” Actually, that’s what the LA Times called “The Crazy Uncle Joe Show,” which has been running at the Groundlings Improv Comedy Theater every Wednesday night at 8:00 for more than a decade. Somehow in the 20 years I’ve been seeing Groundlings shows I have never managed to catch it. Until last week. It knocked my socks off and is deserving of all that hype.

For me, it played on two levels. Yes, it was really funny and fun and entertaining and I found myself laughing a lot. But given my perspective of the science/art thing, I saw much more in it. I’ve literally never seen an improv comedy show like it. Not that it’s different for content, it’s just the sheer frickin’ speed of it. AND the way the actors direct themselves.

My storytelling workshop co-instructor, Brian Palermo, has been performing in the show for eleven years (he’s been in over 95% of the Joe Shows over those years, week after week, month after month — actually, come to think of it, do the math on Malcolm Gladwell’s “10,000 hours” bit from “Outliers” and you’ll realize why Brian is so good). He says the show is, “directed by the format itself,” and he says he sometimes refers to it as, “a particle accelerator of silly.”

space

SPEED AND SELF-DIRECTION

In a nutshell, the show is very simple. There’s seven “players.” The first two actors step forward, the audience tells them what they are doing (something like “performing surgery”) gives them a title of a movie that they don’t act out, only manage to incorporate it at some point (so “Chinatown” might eventually surface with one of the players saying, “I’m so glad they built this new hospital in Chinatown”), then they’re off.

Where it gets amazing is as the scene builds speed the players on the sides “clap in” — one of them claps their hands, two of them take over the stage while the previous pair step aside, then they add themselves to the scene (maybe they are spectators in the gallery watching the operation saying silly comments to each other).

What amazed me was both the speed and self-direction. Improv is based on the core principle of affirmation — that you accept everything your partner says. But when improv is moving slowly or even at a normal pace you can feel that the players are still doing a little bit of critical thinking in their head, trying to figure out what does and doesn’t work about the premise.

With this show it gets going at such a blinding speed and with everyone coming up with ideas on the spot, there literally is zero room for anyone to disagree with anything. It’s like a stampede — if one buffalo in the middle were to suddenly stop, the entire herd would pile up. It has the same feeling.

So a player claps in, directs their partner to stand beside them, then says something like, “I just don’t understand why the surgeon is using children’s scissors.” The other player has to instantly figure out the circumstance (“oh, we’re in the gallery”) and come up with something. There’s no time for them to whisper a plan to each other — they just have to go for it. And if the partner directs them to sit in a chair, they can’t ask why. They just have to go with EVERYTHING (and now we’re getting to the polar opposite of scientists, who want a reason for EVERYTHING).

And here’s the truly crazy part — it goes for a half hour, non-stop. They run it twice, with a break in between. And it builds. Faster and faster. Which causes it to be funnier and funnier. And you realize that negation takes time. This is a show that is designed to ultimately allow zero time for negation.

It REALLY is a spectacle. And regarding the “directed by the format” idea — Brian said to me, “We can’t really direct each other. Many is the time I’ve had an idea and started a new scene with one line only to have it drastically altered by my scene partner’s next line — then IMPROV takes over and you just go with it.”

“You just go with it” — that’s a pretty good phrase to sum up what improv is.

In watching it I felt like it is the ultimate embodiment, fulfillment and embracing of everything improv teaches. After 20 years of seeing shows, this was the one where I felt like, “wow, I finally totally get what this “yes, and …”/affirmation stuff is about.”

space

AND THEN THERE’S SCIENCE

I truly encourage everyone, if you’re in L.A on a Wednesday night, go to a performance of this show. It is an original. The Groundlings are the ones, with this show, who created the “clap in” format as a show, which is now used all over the place. Brian says they got it from Groundlings alum Holly Mandel and an outside teacher, Stan Wells, whom they thank at the top of every show.

And if you’re a scientist, I’m not saying you should be like these people. In fact, you better not be. Not even for a few days — you’d destroy your career if you were this non-negating. I’m only saying come to the show and look at it on two levels. At the surface level, have fun and laugh. But at a deeper level, think about how completely different the behavior is, and what it does to your brain mechanistically to shut down the negation process even for a short while.

People have talked about the scientific method for centuries. It’s time to experiment with it by messing behaviorally with people’s brains in new ways.

#276) Animal Truthiness: Fudging a Chimp Movie

May 6th, 2013

Ben Affleck may make his movies, “in the spirit of the truth,” but what about when nature filmmakers do it?

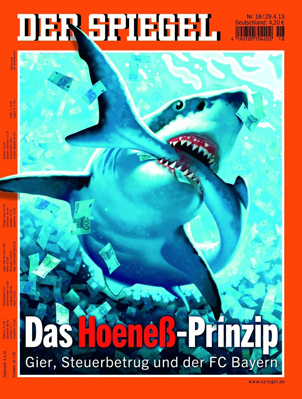

SHARK EATING ITS OWN TAIL IN SEA OF MONEY. What channel could Der Spiegel possibly be referring to?

space

IN THE SPIRIT OF THE TRUTH?

I loved it last fall when Ben Affleck at the Toronto Film Festival, talking about the accuracy of his movie, “Argo” said it was made, “in the spirit of the truth.” That is one of the most wonderfully carefree quotes ever about accuracy, a topic that really shouldn’t be considered carefree. It’s the equivalent of, “she’s kinda pregnant.” Either we can trust the accuracy of a movie or we can’t. Which is it?

Who knows what to make of today’s information-saturated, and increasingly error-saturated, world (see David H. Freedman’s excellent article, “Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science” which pulls back the covers on the accuracy problem in the medical science world).

When it comes to the accurate depiction of nature in films, veteran nature filmmaker Chris Palmer wrote a really great book on the issue called, “Shooting in the Wild.” But his pleas for genuine reality in the presentation of nature appear ignored by a couple of British nature filmmakers who concocted a film about chimpanzee behavior in the wild that German critics have just pointed out is kinda bogus.

And sadly guess who was one of the advisors on the project — the recently tainted Jane Goodall.

space