#365) “The Double Helix:” James Watson Was As Savvy As George Lucas

August 12th, 2014

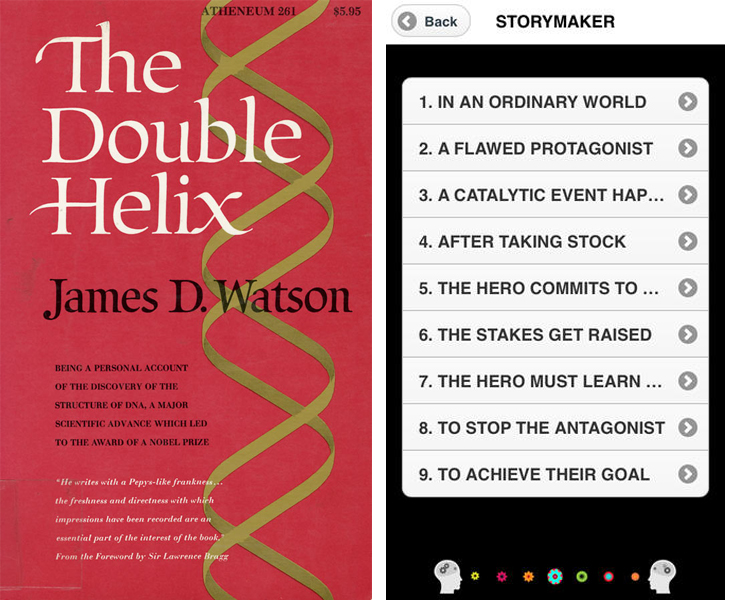

Whether he ever knew of Joseph Campbell‘s work or not, when James Watson wrote “The Double Helix,” he was as tapped in to the template of the Hero’s Journey as George Lucas when he created “Star Wars.” In this guest essay, my Benshi editor of the past year, Steph Yin, breaks down “The Double Helix,” using both the Logline Maker of our Connection Storymaker app, as well as the Story Cycle found in books like “Winning the Story Wars.” I read “The Double Helix” as an undergraduate, a long time ago, yet it still sticks with me. There’s a reason for that, as Steph demonstrates here.

THE DOUBLE HELIX. This classic tale of scientific discovery, like so many other timeless stories, fits snugly into the Hero’s Journey.

THE MOLECULAR BIOLOGIST’S JOURNEY

Steph Yin graduated from Brown University last year and has been working part-time with me since then, running the Benshi and helping with my social media efforts. She’s a superstar who is headed to NYU in a couple weeks to begin working on her master’s degree in science journalism with this year’s Pulitzer Prize winner Dan Fagin. In January she helped me run the version of our Connection Storymaker Workshop at the SICB meeting in Austin, which gave us a chance to have in-depth conversations about the elements in our Connection Storymaker app.

Out of those chats came the realization that James Watson’s “The Double Helix” is a classic tale of a singular protagonist on a journey in search of a golden chalice in which he overcomes many obstacles to eventually succeed. More importantly, it’s one of the best-told stories from the world of science ever. We both wondered how closely Watson’s tale matches the template of the Hero’s Journey as originally described by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 foundational work, “Hero with a Thousand Faces.” Turns out it’s amazingly close, in addition to embodying a number of other great aspects of effective broad communication. The following is Steph’s analysis of “The Double Helix” from this perspective.

COMPARISON: THE ABT VS. THE LOGLINE MAKER

When Randy suggested that I read “The Double Helix” and investigate his suspicion that the story fit the classic Hero’s Journey model, I took it as an opportunity to grow two flowers with one seed. I had been meaning to read “The Double Helix” for ages, and had also just successfully used the logline maker in a serious way for the first time.

Though I had been working with Randy for nearly half a year, I could never fully appreciate the logline maker; some part of it always felt a bit contrived. After this recent success, I was hungry to apply the Hero’s Journey in different ways and flesh out my understanding of its potential.

Up until that point, the Storymaker’s logline template, based on the Hero’s Journey, had met with varying levels of success in Randy’s Connection Storymaker Workshops. While people intuitively grasped the “ABT” (and, but, therefore) storytelling template, they had a little more trouble trusting the Hero’s Journey template.

Randy believed this happened in part because once people generally settled on the story they wanted to tell, they were reluctant to modify it. While most stories by nature fit the ABT model easily, the Hero’s Journey takes a little more finagling. So when asked to use it as a template, people tend to find the exercise stifling and a bit forced.

The ABT is a practical and versatile tool. It can tell the story of an environmental hero who saves a watershed, explain how subatomic particles collide, or interpret a Mars rover discovery. The logline is much more human-centric—using more theatrical terms like “protagonist” and “ordinary world.” As a result it can seem not just distant, but downright flaky, even, to research scientists. Randy and I decided that for scientists to grasp the potential relevance of the logline, we needed a strong example of how a story of scientific research could fit within its framework (cue “The Double Helix!”).

BREAKING DOWN “THE DOUBLE HELIX”

Reading “The Double Helix,” I was struck by the candid nature of Watson’s writing. He became immediately familiar to me, and this, in turn, made reading the book much more enjoyable—as if I were reading letters from a friend. Watson has all the trappings of a flawed protagonist: he is young, foolhardy, searching for fast shortcuts to fame and seduced by the world of the educated, European socialites around him. His flaws set him up to undergo the Hero’s Journey.

Below is a summary of this journey, using the language of the Connection Storymaker logline:

In an ordinary world, a flawed protagonist: In an ordinary world, James Watson is a young scientist at the University of Chicago, primarily interested in studying birds, impatient for fame and looking for career shortcuts (in particular, avoiding taking any advanced chemistry, physics or math courses).

Feeling unfulfilled by ornithology, he becomes curious about how genes work. He starts grad school at Indiana University, advised by microbiologist Salvador Luria. At this point, he is interested in studying DNA but still hoping to avoid learning any deep chemistry.

A catalytic event happens: He gets his life upended when, in the spring of 1951, he goes to a conference in Naples and hears a talk on X-ray diffraction of DNA by Maurice Wilkins, a physicist and molecular biologist at King’s College. Around the same time, Watson realizes that these conferences were as much a gateway into a fashionable social scene as they were an entry into academia. He writes, “an important truth was slowly entering my head: a scientist’s life might be interesting socially as well as intellectually.”

After taking stock, the hero commits to action: After taking stock, Watson becomes determined to learn chemistry and solve the structure of DNA. He decides to go to the University of Cambridge to learn X-ray crystallography. There, he meets and bonds with Francis Crick, who is also interested in DNA. Watson writes, “From my first day in the lab I knew I would not leave Cambridge for a long time. Departing would be idiocy, for I had immediately discovered the fun of talking to Francis Crick. Finding someone in Max [Perutz]’s lab who knew that DNA was more important than proteins was real luck… Our lunch conversations quickly centered on how genes were put together.”

Together, Watson and Crick commit to finding the structure of DNA using a combination of X-ray photography and model building, a method that had recently been used by the biochemist Linus Pauling to understand the structure of proteins.“Within a few days after my arrival, we knew what to do: imitate Linus Pauling and beat him at his own game,” writes Watson. “Now, with me around the lab always wanting to talk about genes, Francis no longer kept his thoughts about DNA in a back recess of his brain… No one should mind if, by spending only a few hours a week thinking about DNA, he helped me solve a smashingly important problem.”

The stakes get raised: After a while, Watson and Crick think they have stumbled across a breakthrough. They believe DNA is a three-chain helix with phosphate groups held together by Mg2+ ions. However, when Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin (who were studying DNA at the same time) visit Cambridge at Watson and Crick’s request, they quickly find holes in this three-chain theory. Their idea thoroughly shot down, Watson and Crick are discredited, and their superiors order them to stop spending their time on DNA. “By this time neither of us really wanted to look at our model. All its glamor vanished, and the crudely improvised phosphorus atoms gave no hint that they would ever neatly fit into something of value,” writes Watson. “… the decision was thus passed on to Max that Francis and I must give up DNA.”

The hero must learn the lesson, to stop the antagonist and achieve the goal: In order to find the structure of DNA before his competitors (Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, Linus Pauling), Watson must learn to take his time, cultivate a deeper learning of chemistry and mathematics and resist his temptations to take shortcuts or rush to conclusions. For a while, Watson and Crick do their DNA research on the down-low while making progress on their primary research (Watson focused on the structure of tobacco mosaic virus).

During this time, Watson devotes a great amount of time to learning chemistry—combing through scholarly journals and seminal books on the topic. “I used the dark and chilly days to learn more theoretical chemistry or to leaf through journals, hoping that possibly there existed a forgotten clue to DNA,” he writes. “The book I poked open the most was Francis’ copy of ‘The Nature of the Chemical Bond.’ Increasingly often, when Francis needed to look up a crucial bond length, it would turn up on the quarter bench of lab space that John [Kendrew] had given to me for experimental work.” Watson hones his X-ray photography skills, thinks about DNA late into his evenings and continually checks with reference books and colleagues to make sure his chemistry is correct.

By the time he and Crick believe again that they have cracked DNA’s structure (which, of course, this time they had), they are vigilant about checking their assumptions and obtaining exact coordinates before spilling the news, having learned from their earlier fiasco with Wilkins and Franklin. “Keeping King’s in the dark made sense until exact coordinates had been obtained for all the atoms. It was all too easy to fudge a successful series of atomic contacts so that, while each looked almost acceptable, the whole collection was energetically impossible,” writes Watson. “…Thus the next several days were to be spent using a plumb line and a measuring stick to obtain the relative positions of all atoms in a single nucleotide.”

By the end of the book, Watson and Crick have successfully predicted the structure of DNA, and it seems Watson has matured both as a scientist (in his deeper grasp on chemistry and math, as well as in his patience and restraint) and person (who is perhaps no longer as taken with instant fame and the charms of the social elite).

He ends the book in Paris, on a trip with his sister. In the last sentences of “The Double Helix,” he writes, “… now I was alone, looking at the long-haired girls near St. Germain des Prés and knowing they were not for me. I was twenty-five and too old to be unusual.” On that note, our hero turned the page toward a new journey.