#326) SICB Plenary: Trying to Sway Tough Science Minds

January 6th, 2014

Tough crowd. Bred to negate. But they understand something important: large scale change takes long term effort. Nevertheless, they could all stand to learn more about Joseph Campbell and what he had to say about the telling of stories. The best place to start is Dorie‘s section of our book, “Connection.”

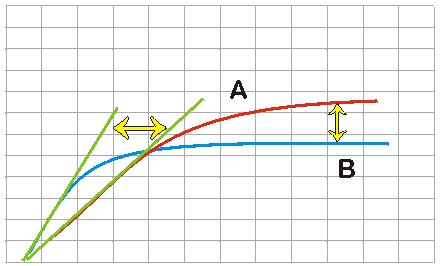

AUDIENCES CAN BE LIKE ENZYME KINETICS. The blue B curve would be the business and Hollywood communities who are quick to adopt new ideas, but have too short of an attention span to gain full value from the ideas. The red A curve would be research scientists like the folks at SICB who are VERY resistant to change, but have the long attention span, enabling them to eventually get the full value of a new idea (assuming everyone lives long enough to see it happen).

BRED TO NEGATE

Okay, before we get started here, take a look at this heading, “BRED TO NEGATE” and think about what your immediate response to it is. If your first thought is, “Well, I wouldn’t really say scientists are “bred to negate,” just think for a second whether you realize you are starting by wanting to negate that heading. I’m just asking you to consider whether you’re really aware of how much you start just about every thought with a process of negation. Not saying it’s wrong. Just asking if you’re aware of it (which was a major part of my book, “Don’t Be Such a Scientist“). That’s all for now.

I just had a really wonderful 3 days in Austin where I gave the Opening Plenary at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology to about 700 scientists, then we ran a 90 minute sample version of our Connection Storymaker Workshop. All 16 slots for the workshop were filled, but in addition, about another 40 people showed up to observe, which was cool and impressive.

I used to be a member of SICB when it was The American Society of Zoologists so there was an element of “old home week,” to my visit — especially as my Ph.D. advisor, Ken Sebens, introduced me for the big talk by calling me “the Jane Goodall of sea squirts” (she lived in the wild with her primates she was studying, I spent 6 to 8 hours a day underwater on the Great Barrier Reef with the sea squirts I was studying).

Lots of fun reunions with people — some I hadn’t seen for over 20 years, but make no mistake, SICB is a tough crowd. And they showed it after my big talk. Unlike audiences I speak to from the business community (who are on at one end of the acceptance spectrum shown below) there was a strongly negative, critical tone to this group. Which is a good thing in terms of them valuing truth and accuracy over all else, but is also sort of life-draining when it comes to broad communication.

In my first book I talked at length about the need to balance negativity and positivity. It does no good to be a brainless Hollywood producer who says yes to everything (it is the driving force behind $100 million movies that flop). But just the same, starting all conversations with “no” simply does not work for communication. It is great and essential for good scientific research, but when it comes time to communicate, the process just is not as simple as negating things to pieces. Sorry. It just isn’t. And you really should trust me on this (before saying, “No, I think that…”). I’ve put in a lot of years in two professions. And yet … I could feel that a lot of the audience didn’t care. They needed to prove these things to themselves. And yet aren’t interested in spending 20 years in Hollywood to fully learn it. Which really doesn’t add up in the end.

THE REASON EVERYTHING YOU SAY IS WRONG IS …

I seriously have never sensed this vibe from an audience as clearly as I did on Friday evening. There were lots of positive and enthusiastic comments after the talk, but even the three question/comments asked in the Q&A had this tone of, “The way in which you’re wrong here is …”

One question was about excessive use of the Hero’s Journey template leading to homogenization, one was about my failing to grasp how “special” science is (when the questioner actually failed to grasp Joseph Campbell’s use of the word “special” which I had clearly explained), and the third was disagreeing with my low opinion of the “and, and, and” structure.

As a group, it was just SO different than what I’m accustomed to. When I speak at CDC, at the Society for Hospital Leadership, with business groups, with Hollywood folks, there is a basic tone of, “this is great, can you say more about how we can put this knowledge to use.” But with this group … the basic tone was sort of, “I don’t know … I’m going to have to think this stuff through.”

Very conservative. Anti-change. Anti-innovation.

And why do I say this so confidently — because I was a member. I know it all too well. Tough crowd. When it ended, a group of about 20 people came up who were mostly great, but the first to talk was a Scottish grad student who rather tersely pointed out I had no data, no controlled studies, no published peer-reviewed papers — nothing but anecdotes and speculation … to which all I can say is, dude, communication is not the same as research — trust me, I’ve done both, you haven’t, I know what I’m talking about here.

If your communication strategy is going to be based ONLY on “facts” that arise from data sets and controlled studies you’re going to have very little to say at the podium. It just isn’t the same. There’s a real world element that is different from the cloistered setting of the research laboratory.

THE SPECTRUM OF AUDIENCE CHEMISTRY

SCIENTISTS PUBLIC HEALTH BUSINESS COMMUNITY

I——————————————————————————I——————————————————————————–I

(NEGATION-DRIVEN) (AFFIRMATION-DRIVEN)

So I’m not looking to argue about this. Don’t waste your time. I’m just telling you this is what I see. I talk to all these different audiences. They end up falling along a spectrum. At one end there is the business and Hollywood crowd. They are full of energy, excitement, and eagerness to try new ideas. BUT … it’s kind of hard to get them to stay focused and actually take an idea the whole distance. Also, while they gobble up the storytelling stuff, they really have little interest in this thing called “accuracy.” They just want to get people excited so they can make money.

In the middle is the public health crowd — much more concerned that their public health facts get communicated in an accurate manner, but also, because they have the word PUBLIC in their field of work, feel strongly compelled to communicate effectively.

And then there are the scientists … I beat them up enough in my first book, “Don’t Be Such a Scientist.” They are just tough. But on the up side, I felt one thing very clearly after my talk that gave me hope, which is that as I explained the need for “narrative training” and the fact that it is something that requires a long term perspective and commitment … THAT is where I saw a ray of inspiration. They get it on that front. Hollywood and the business world, it is well known, have zero interest in anything beyond the next fiscal year. This is how science differs. It comes at the cost of that grouchy, negating attitude in the short term. But it is eventually balanced out by this ability to think in the long term.

THE SICB COMMUNICATORS JOURNEY (TWICE TOLD)

So just to prove that despite this negating atmosphere, there were still more than enough awesome wonderful enthusiastic people, two of them on their own downloaded our Connection Storymaker app, then used the Logline Maker to tell MY story at SICB and emailed their stories to me, which is hilarious. Thank goodness for these people. They give me hope for the long term, even with tough crowds like SICB.