#324) GAVIN SCHMIDT vs. TAMSIN EDWARDS on climate science advocacy: I’m with Gavin

December 27th, 2013

In a perfect world, I’m with Tamsin Edwards (who says scientists should stay clear of all potential controversy). But we don’t live in a perfect world. Gavin Schmidt knows this and articulated it well in his recent AGU talk. He argued that yes, scientists should be willing to speak up. I want to just add a few of my thoughts on this issue based on what I witnessed in my years of coral reef ecology and coral reef conservation. Bottom line: I’m in total agreement.

#323) All I want for Christmas is an Unboring Planet

December 23rd, 2013

Der Spiegel did a 10 question interview with me asking why I feel that global warming is the most “bo-ho-horing” topic in the history of humanity. Boring is not a good thing, but there is hope. It’s called “Narrative Training.” Which now completes my couplet of two articles this month: PROBLEM – BOREDOM (Der Spiegel), SOLUTION – NARRATIVE TRAINING (Science).

YES, THERE IS HOPE. It exists in the form of “Narrative Training.” Teach the good people to not be boring and you can change the world. (the catch is that most of the truly good people I know are kinda reeeaally boring)

HOPE FOR HUMANITY (KIND OF)

Got a couple fun things here. First, the German magazine Der Spiegel let me vent my spleen a bit on the innate tendency towards boredom among humanity in general in an article titled, “Filmmaker Randy Olson: Climate Change is Bo-Ho-Horing.”

Actually, the original German version from Axel Bojanowski is I think it much better than their English translation. A German friend of mine read it and said, “It’s very Douglas Adams.” Which sounded great to me since Douglas Adams is the guy who solved the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything, which turned out to be 42. I’m afraid the English version feels a little less fun, and a lot more blunt. Something was clearly lost in translation.

Second, my letter in Science of three weeks ago did exactly what I had hoped — it flushed out the very sort of fellow from the humanities whom I knew must exist, yet had no way of finding. His name is Barry Woods, he is an associate professor in the English Department at the University of Houston, and he teaches an undergraduate interdisciplinary course that is hugely popular and filled to capacity every year titled, “COSMIC NARRATIVES: A history of the Universe from its beginning to the present.”

Bingo. THAT is the guy I was hoping to meet — someone who has converged on the same answer as I (which is NARRATIVE INSTINCT), but from the humanities rather than the sciences. We had a great hour long phone chat then traded a bunch of emails. I knew his sort of thinking was out there, but it’s so hard to cross disciplines and find it.

For starters, he loved my term, “storyphobia,” in my letter because he has learned the same thing — scientists hate the word “story,” and yet are perfectly comfortable with the word, “narrative.” He sent me his syllabus. Every section is “the narrative” of this or that. And it’s easy to see the problem. If you replaced the word “narrative” with “story,” it would indeed sound pretty light weight — the first section of, “What are cosmic narratives? ” becomes, “What are cosmic stories ?” — the former sounds analytical, the latter sounds like Superman.

After matching notes on a whole bunch of things, my final question to him was, “Do you think narrative structure is the best possible antidote to being boring?” His answer was yes, he agrees.

And that’s it. I’ve been exploring one major question for the past 20 years of my life.

What makes the world boring and how do we avoid it?

There you go. The answer is as simple as 42.

#322) Revkin: On the Right Track with Global Warming and Simple Storytelling Problem

December 16th, 2013

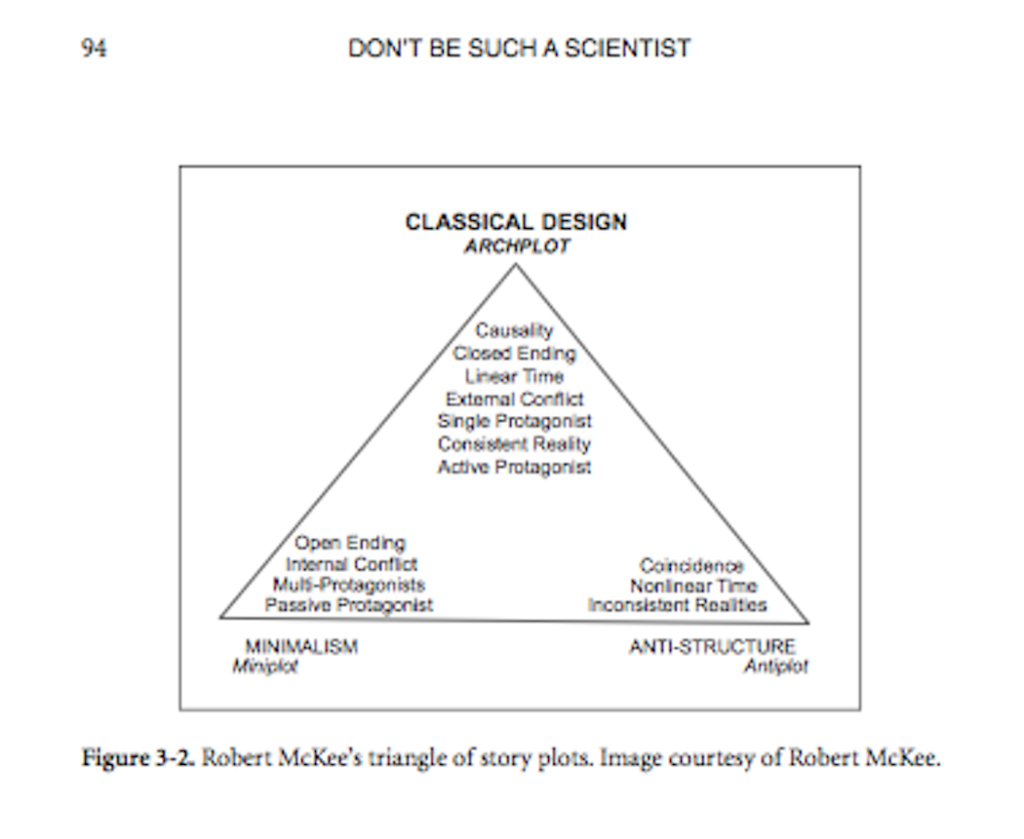

Andy Revkin has a great post today asking the question of whether “the villain” for global warming isn’t so diffuse and hard to define that we are crippled in trying to get the masses to focus and rally. That is my kind of thinking. Just look at Robert McKee‘s Triangle — it’s right there. ARCHPLOT is how you reach the masses the best. It calls for a single protagonist, and just the same, a single antagonist. Anything short of this starts to drift you down into the artsy world of MINIPLOT, and thus a smaller audience.

That’s sort of the question Andy Revkin posed today in his essay titled, “Can We Respond to Problems like Global Warming Where There’s ‘No Simple Villain’?”

And it’s even more than just that the threat is diffuse and multi-facted. It’s also the famous Pogo quote that “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

I won’t do my usual grandstanding here. I only encourage you to read Andy’s piece — he’s on the right track.

#321) VIDEO: Chris Palmer is a Voice for the Future of Nature

December 12th, 2013

For nature to stand any chance of surviving humanity’s reign, the media will have to play a major role. At this point we are a media-driven species. This means the media needs the right approach to understanding wildlife — which means not making animals into clown figures, not concocting untrue scenarios (like lemmings and cliffs), and not exploiting the hell out of every piece of violent, blood-soaked scene of natural (and staged) predation. Towards this end, Chris Palmer presents the clearest, most compelling voice articulating and advocating these values in wildlife filmmaking. He’s a great guy with a great mission, and everyone interested in protecting nature should watch this new video from him, hosted by Alexandra Cousteau, based on his excellent book, Shooting in the Wild.

THE TRUTH ABOUT LEMMINGS. Among many wildlife filmmaking falsehoods Chris Palmer and Alexandra Cousteau try to set straight in their new 25 minute video, “Shooting in the Wild,” is that lemmings don’t jump off cliffs (though they may be thrown off cliffs for a Disney movie).

A VOICE IN THE COMMERCIAL WILDERNESS.

I have a few pet topics here on the Benshi that recur frequently. One of them is the importance of veteran wildlife filmmaker Chris Palmer’s work to establish a set of ethics for wildlife filmmakers. The whole idea of “ethics” seems old fashioned in today’s internet-obsessed world where there seems to be a belief that everything can just be left up to the knowledge of “the crowd” with no need for anyone to speak up. Which is misguided. And the reason why both his acclaimed book, Shooting in the Wild, and this film need to be promoted widely.

In particular, what I have consistently admired about Chris has been his work in speaking out against the exploitative practices of the Discovery Channel with their Shark Week bonanza of the past 25 years. He has written essays in the Huffington Post, and I have admired those essays in posts here and here.

And guess what he says in the video — this past year Discovery has finally shifted their tone from scare mongering about sharks to concern about their worldwide decimation. About time, dudes (just don’t get me started on all the stories I have from my USC film school classmates who have had to work on the countless crap shows Discovery and National Geographic have produced over the years in their desperate search for ratings). I have to think Chris’s voice has been a major factor pushing Discovery to develop a little bit of a conscience.

A MAN WHO KNOWS HIS JOSEPH CAMPBELL

What is very cool about the video is how it opens with basically “the flawed protagonist,” of Joseph Campbell‘s “Hero’s Journey” (which Dorie Barton adapted into her Logline Maker in our Connection Storymaker app). Instead of talking from some high and mighty position as a virtuous wildlife filmmaker who has never committed a sin, looking down on the heathens who are ruining nature with their cameras (which would be the idea of an “unflawed protagonist”), Chris begins by admitting he has taken part in the very unethical acts that he now is speaking out against.

Which is powerful and persuasive.

He tells of staging shots and misleading viewers (granted, long ago in his filmmaking career) for the sake of “telling a better story.” His transgressions back then are minor compared to the trends towards “animal porn” that eventually emerged when wildlife filmmakers began to realize how much money there was in showing sharks and lions tearing wildlife to pieces (not to mention footage of monkey sex and every other imaginable animal orgy– btw, a friend JUST told me about being contacted by a researcher from one of those channels seeking footage on “rape” in any species of animal — how lovely).

Chris is now a professor at American University sharing his years of knowledge with students and producing superstars like recent graduate Jackie Yeary who ended up being part of our social media team last summer for the release of our book, Connection.

So if you want to listen to voices that are truly standing up for the proper and ethical approach to nature, you have to read his book, follow his blog, and also follow the great work of a younger voice from South Africa (now residing in NYC), Adam Welz, who takes on the same issues on his excellent and popular blog, Nature Up for the Guardian (he has a great piece this week on how some US environmental websites have become infested with cutesy cat and dog stories — and in a similar “flawed protagonist” move he opens with a photo of his own cat — hey, we’re all human!).

#320) My Letter in Science: What a short strange trip it’s been

December 9th, 2013

This week I have a letter in Science — the culmination of a rather amazing series of highs and lows.

THE FACE OF INNOVATION. Megan Bailiff was the one responsible for our very effective plenary panel at CERF on November 5 which produced this Letter in Science this week. She is the one who changed the course of events at the very start by saying to me, “Everyone has had enough of the standard droning panel discussions — we want you to try something different using your narrative approach — even if it fails — we just want something new and different.”

LIFE IS GREAT, TERRIBLE, GREAT, TERRIBLE, GREAT …

My Letter in Science this week tells a brief, cool story about the making of our Plenary Panel at CERF. But here’s the full story, in all it’s roller coaster painful detail.

HIGH: INVITATION – Last summer my good friend Megan Bailiff asked me to join a plenary panel at the November meeting of the Coastal and Estuarine Research Foundation, telling me it would be a great chance to promote my new book and app, so I agreed.

LOW: MIX-UP – In September I looked at the website for the event — the panel was about Sea Level Rise with zero mention of communication, and I looked like a doofus up against two world experts on Sea Level Rise since I know nothing on the subject.

HIGH: CLARITY – I called Megan, fairly grouchy, saying, “What have you gotten me into?” but she explained that was exactly the idea — she wanted me to “do a makeover on the panel” as she assured me the two panelists were DYING to have me completely overturn their standard presentations, which sounded like fun to me.

LOW: GET LOST – Turned out the two panelists had no interest in having me experiment on them (for which I couldn’t blame them), they had limited time to prepare for the event, one of them was out of the country, and within a couple days we were caught up in an email spat over my novel ideas and their preference for the usual thing.

REALLY LOW: I QUIT – After viewing their combined 94 slides and sensing their resistance, I did the dignified thing — I quit. I called Megan. She was graceful in accepting my withdrawal, only conveying sadness as she had such high hopes, and then …

HIGH: I UNQUIT – Honest to goodness — just before I hung up, an email popped up from one of the two panelists — they had discussed it, decided they were senior enough that they could endure one major debacle in their career, so why not — let’s give it a shot. Within ten minutes I was on Skype with him and we were instantly connecting on every question — I would ask, “Have you got a story that shows this …” he would answer, “Yes, I know exactly what you want, yes, I’ve got that.” The vision was springing together.

LOW: ABANDONMENT – A few weeks before the meeting Megan sent us an apologetic email saying she had to travel to Fiji in November and wouldn’t be able to attend the meeting to see our panel.

HIGH: ANTICIPATION – The three of us panelists met at the hotel the day before the big event, all genuinely excited, more nervous than any of us had been in years in preparation for a presentation. We had put in a lot of effort and figured something good would have to come of it, but still, you never can tell how these things can go seriously wrong.

SHOCKING LOW: BOATING ACCIDENT – Mike Orbach showed up for dinner shaken, having just received a text message from Megan — she was on her way to Brisbane, Australia, from Fiji where she had been involved in a serious boating accident, so severe they couldn’t handle her injuries at the hospitals in Fiji.

SHOCKING HIGH: GREAT PERFORMANCE – With her spirit hanging over the event, we put on the panel, and it exceeded our expectations producing incredible raves from the 1,000 audience members (detailed here). Basically our grand experiment worked!

HORRIFYING LOW: NEAR FATALITY – Later that day the details emerged about Megan’s accident — she nearly lost her life — she was run over by a boat while snorkeling in front of it — the impact of the bow fractured her skull and shattered her shoulder then the boat veered and ran over her — the propeller hit her back, breaking ribs, puncturing a lung, crushing her left femur, slicing her calf muscle and heel. She was eventually “jet-evaced” to Brisbane (which has a world class trauma center) where she underwent 7 operations in 8 days.

THE FINAL CONSOLATION PRIZE: MY LETTER IN SCIENCE – So … after all that … Megan is now back in San Diego where she’s in for months of further work and physical therapy, however she’s already stunned the doctors by recovering much faster than expected. In just a month her shoulder bones are healing and ahead of all their predictions. The thing that I can’t get over in my conversations with her is how consistently upbeat and positive she is with her attitude. Not one complaint, just focused on moving forward in her physical therapy.

And guess what — this is not a coincidence — that this person who came to the planning of a big event with the attitude of “let’s try something new” is also the fighter who so impresses the doctors.

Anyhow, wow. What a short, strange trip. The event that nearly melted down turned out to be one of the coolest experiences of my entire professional life (you can view the entire CERF plenary panel here). Megan ended up being “incredibly lucky” to have survived such a horrific accident (though as she and I have agreed, it would have been “incredibly luckier” to have never been hit by the boat).

Overall, the entire experience tracks back to Megan’s initial desire to do something new. This is the spirit that is desperately needed in science and environmental communication. The world has changed. The audiences have changed. We can’t go on doing the same old dull presentations. This stuff is too important. There has to be innovation. For this, we need more people like Megan Bailiff who are willing to push things in that direction.

I really mean this.

#319) My Letter in Science this Week

December 6th, 2013

I have a Letter in Science Magazine this week (Dec. 6 issue). It presents (rather concisely) my agenda for the near future — to introduce the idea of “Narrative Training” at the very beginning levels of the science world. This will also be the message of my Opening Plenary on January 3 at the meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in Austin.

TELL ME A STORY. That’s what it’s all about in the end.

MILKING THE CERF THING

As if it wasn’t enough to run a successful event, I apparently felt the need to tell the whole world about our CERF panel last month. But why not — it exemplified everything I’ve been learning for the past quarter century.

In the workshops I run with physicians and the Society for Hospital Leadership we do an exercise (that I learned from my good buddy Maggi Cary) where we have the doctors, “Tell the story of the one day you felt all your years of training coming together to enable you to do something significant.” For most of them it’s an E.R. experience and their stories are amazing.

I was asked the other day what that experience would be for me. The answer is that CERF panel. It was a synthesis of all my 25 years of narrative training. And that’s why I felt it was important enough to write up for Science.