#229) Occupy Success Shows Why Environmentalism Fails/Bores

September 17th, 2012

Occupy visceral. Environmentalism cerebral. Occupy succeed. Environmentalism fail.

WE CAME, WE SAW, WE OCCUPIED. There was minimal thinking, maximal acting involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement. It worked. It had an impact. It moved the conversation. When’s the last time the environmental movement moved the conservation?

WE CAME, WE SAW, WE OCCUPIED. There was minimal thinking, maximal acting involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement. It worked. It had an impact. It moved the conversation. When’s the last time the environmental movement moved the conservation?

yay

JUST DID IT

About a year ago I was out to dinner with some folks in Portland. Someone began talking about some crazy people in New York City who for the past few days had organized an “Occupy Wall Street” movement. One particularly know-it-all person spoke up, saying that the whole effort was stupid and an unfortunate waste of everyone’s time because, “they don’t have a clear action plan — they’ll never amount to anything.” Bottom line, you shouldn’t act on anything until you’ve carefully thought it through.

Within days EVERYONE was talking about the Occupy movement as it spread to other cities. But a lot of the news pundits, like my favorite Chris Matthews, echoed the same predictions of inevitable failure because they hadn’t “thought things through” — i.e. they didn’t have a plan.

Yeah? Well, sometimes not thinking things through can be more powerful than bringing in teams of brainiacs to analyze, negate, and constrain what was initially a good idea. The way that conservation foundations have, producing a movement that is widely labeled as “failed” (not by me — by lots of essays, including the excellent report from Sarah Hansen of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy earlier this year).

bob

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED, LOUDLY

So it’s a year later. The Occupy Movement succeeded. Yes, their ranks are now thin, but an article in today’s USA Today quotes Hector-Cordero-Guzman, a City University of New York sociologist who has studied the movement and says, “It has made an impact. Many of its complaints and some of its rhetoric — notably “We are the 99%!” — have become the stuff of mainstream politics. Occupy, he says, “changed the political conversation from where it was last summer. Income inequality, money in politics, the influence of Wall Street — you can see those now in the presidential campaign. You see it in questions about Bain Capital and about Mitt Romney’s tax returns.”

Mission accomplished. From a ragtag bunch with no clear “action plan.” They succeeded in communicating effectively, not by holding weekend retreats at expensive lodges with paid facilitators and assembling phone book-thick plans of action, but just by DOING it. Not by thinking, by acting.

The entire environmental movement today is run by the money which comes from cautious, conservative foundations who agonize over every dollar they hand out. You can’t make a good idea take off quickly in the conservation world. Everything is slowed down, scrutinized, thought through, drained of life, and then eventually squeaked out in the most boring of ways. In other words, Dullsville.

Congratulations to the Occupy Movement. Who cares about their future — they may not have one. They already have a solid past. And it has involved that most precious of commodities: excitement.

#228) In Praise of Tardigrades: A Perfect Video with a Perfect Spokesman

September 7th, 2012

This is an awesome little video about an awesome little creature. Tardigrades have always been my second favorite invertebrate (beaten only by octopus). If you’ve got a brown thumb when it comes to taking care of nature, this is your creature. They are a prime example of both cryobiosis and cryptobiosis. You can bake ’em, freeze ’em, dry ’em out, and send ’em into space — they won’t bat a water bear eyelash. Tardigrades are perhaps the most mind-bending organism on the planet, and the tardigrade lover in this video is the perfect match for them.

QUIRKY IS AS QUIRKY DOES. It’s Friday. Do something to alter your consciousness, then watch this wonderful 8 minute video that has perfect casting, matching a guy who clearly thinks and acts just like a Tardigrade.

yikes

WATER BEAR LOVERS UNITE!

Wow. If you were born when I first got to know water bears, you’d be 36 years old. Of all the creatures we met in the incredible year-long invertebrate biology course I had the privilege of taking at the University of Washington (ZOOLOGY 433/434 taught by the great Alan Kohn and the late Paul Illg— I still have my notebooks from the course!), Tardigrades (or water bears) were truly the most mind expanding. As the humble tardigrade lover in this video explains, they may or may not have originated here on planet Earth. Who knows. They can withstand 300 degrees Fahrenheit. You can dry them out, put them in a dish on a shelf, come back a decade later, hit them with water, and presto, back to life. Tougher than the hardiest house plant.

But even better is this video. Perfect casting, perfect editing, perfect music scoring, a tour de force of humbleness. Talk about trust and likeability — I totally trust this guy to tell me the truth about tardigrades, and I like that he doesn’t play to the camera as if he’s hoping to get his own show on Discovery. In fact, this is the very sort of guy who ought to have his own show. He’s awesome.

#227) Bill Maher: An Important Voice for Climate Change

September 4th, 2012

Bill sets the record straight with a climate skeptic.

BILL MAHER. He seems to be developing a zero tolerance policy for climate skeptics. Which is nice.

spaceghost

FIVE INVESTIGATIONS LATER

A couple years ago I wrote about Bill Maher making a significant blunder on his HBO show “Real Time” when he said, in reference to the Climategate email mess, “… and some of the scientists, yes, were caught fudging a few facts.” Wrong. With the help of climate scientist Mike Mann, we sent the word that there were five investigations that showed there was zero wrong-doing by the scientists. Then last year I ended up backstage at the show and mentioned it to Bill — who held his hands up, saying, “I know, I know, thank you Mister Science,” as he walked away to speak with some beautiful women (classic Bill Maher).

But he heard the message, and last Friday on his show he had a numbnut conservative guest who rather stunningly tried to use the old pseudo-scandal to discredit climate science. In reference to predictions of global warming the numbnut said …

NUMBNUT: “… that has been discredited by the number of emails we’ve seen over in England …”

BILL MAHER: “No, that’s totally discredited bullshit, there are five different commissions that have looked into the East Anglia thing and they all said, ‘nothing there’ it was a fucking typo — this is what you’re hanging it on?”

Bill then proceeded to put his head down on the table, as if ready to bang it in disbelief. It was wonderful, but also very important. He has a large audience. He doesn’t need to know the science of climate change, but it’s important he’s well versed on these basic “talking points” of the climate skeptics. This time he did a great job of putting out the fire immediately and effectively. Progress.

#226) A Mini-Tutorial at the RNC on Narrative Structure

August 31st, 2012

This is nice, and along the lines of my latest hobby horse — grasping the divide between exposition and storytelling.

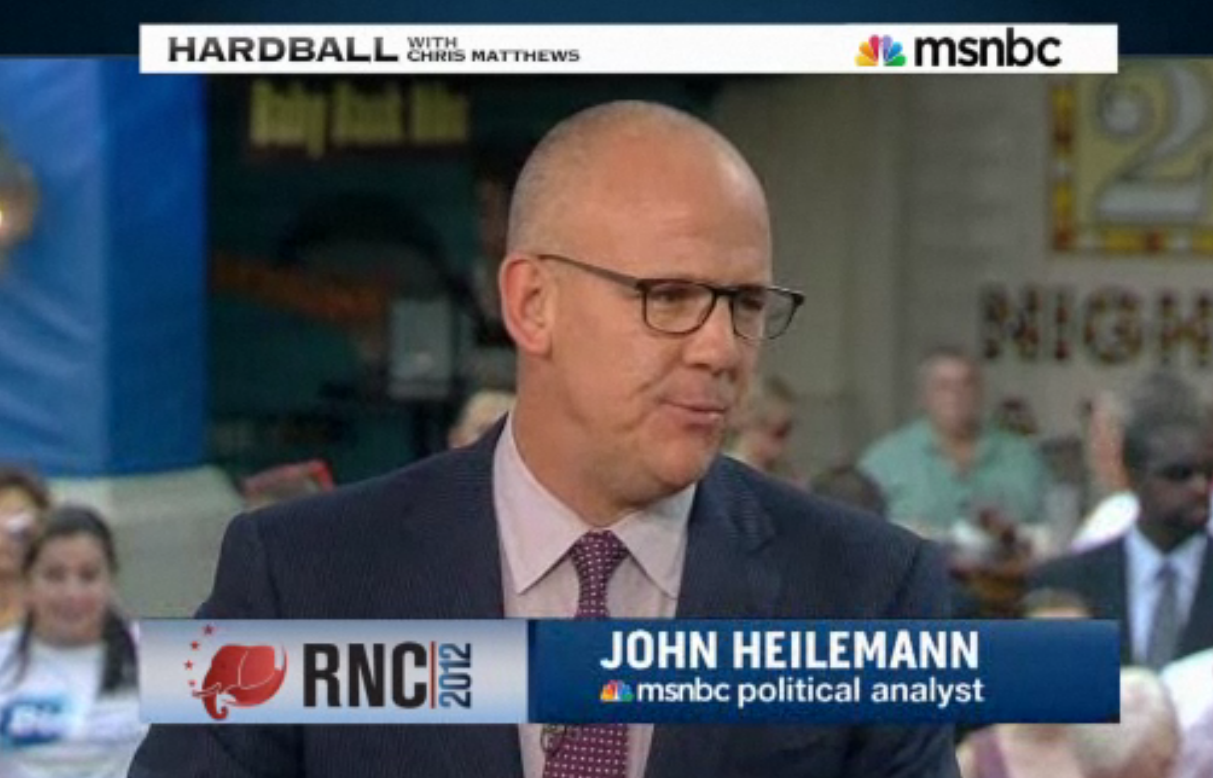

HE SHOULD KNOW. John Heilemann, author of the NY Times #1 bestselling book, “Game Change” in 2010 shares a little bit of narrative wisdom before Mitt Romney’s speech.

space

FOR THE THOUSANDTH TIME … DON’T TELL US, SHOW US

John Heilemann is a sharp guy (his bestselling book “Game Change” with Mark Halperin gave rise to the excellent HBO movie that focused on Sarah Palin). He had some savvy advice for Mitt Romney before his speech last night. Here’s what he said:

“We know the difference between illustration and exposition. We had Ann Romney up there the other night and she did things in exposition — she asserted things in bullet point form — “he’s this, he’s that.” But she didn’t give us illustrative stories — anecdotes — things that reveal him. I think this speech has to be like that — it has to be stories about his father, stories about his kids — I think he’s got to go to the places like, talking about Bain — why was he so successful at that, what did he love about Bain, what does he love about his church, what does he love about his family, and tell people about it in a way that makes him not seem like an android any more — that’s his problem — he’s like HAL 2000, he’s not human — he needs to be human.”

This has become one of the major focal points of my communications workshops — getting scientists (in particular) to grasp the difference between exposition (asserting “things in bullet point form” as Heileman puts it) versus storytelling (or “illustration” as he says — same thing). It comes down to the same old DON’T TELL US, SHOW US. Don’t give us a laundry list, tell us a story that illustrates what you’re talking about.

The bottom line of what he’s saying is that Mitt Romney is a scientist and should read the book, “Don’t Be Such a Scientist.” Although, of course, he isn’t a scientist given his ridiculing of sea level rise last night.

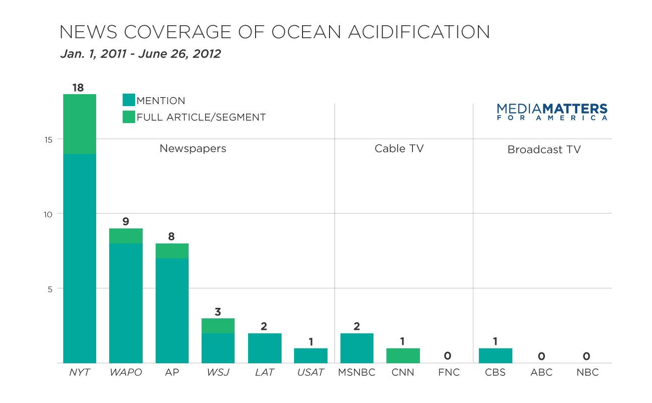

The website Media Matters produced a nice factoid: In the first half of this year, media coverage of the Kardashians was more than 40 times that of the thrilling topic of ocean acidification. Is anyone surprised? Hope not.

DEATH, TAXES AND OCEAN ACIDIFICATION (Name three things you don’t want to hear about).

fin

THE ACID OCEAN REALITY SHOW

A little while back Brett Howell tweeted me this tragi-comic article from Media Matters about the gap in media coverage between the gossip-fodderoids The Kardashians and the not-yet-figured-out-how-to-communicate topic of ocean acidification (big thanks, Brett, sorry it took me a while to get to this, been a busy summer). Turns out there was a 40 times difference for the first half of this year.

The question to ask is, “Does there have to be a gap?” In theory I would say no. But in reality, yep. So you might say, “I guess it’s hopeless,” but I would say, “No, its a question of priorities.” Here’s the basic dilemma …

gone

GOOD, FAST OR CHEAP (PICK TWO)

I’ve run through this before, but this is another case that it applies to. In Hollywood, when you go to your production designer on the set of a movie and say, “I want you to build me the Oval Office,” your production designer will usually reply with, “Okay, good, fast or cheap — pick two. I can make it good and fast, but it’s going to cost you a fortune, I can make it good and cheap, but it’s going to take a few months as I try to recruit friends to donate resources for free, or I can make it for you overnight and for nothing, but you’re gonna have to use your imagination because it ain’t gonna look very good.”

That’s the real world. And the science world, where “fast and cheap” usually rules when it comes to communication (or even slow and cheap!). I know. I was a scientist. Plus I just spoke at a major science meeting (which was a great session, but) where they not only didn’t pay me, they held the meeting in a room with a tiny screen (one third of the size it should have been, using the general rule of thumb they taught us in film school of one inch of screen width per viewer), no speakers for video clips (I had to hold the microphone to my laptop speaker), and no wireless microphone for the presenter. That, to me, is a giant statement of, “We really don’t give a crap if anyone can hear or see you, just show up and do your dog and pony show, whatever.” That’s the science world for you. (and today there’s no excuse given the easy access to examples of how to do it right with all the TED Talks available online, plus this was at a major convention center which could provide bigger screens for starters if anyone asked, but I’m guessing no one even asked — scientists just don’t care about communication)

space

GOOD COMMUNICATION COSTS

That’s all I can tell you. Good, fast or cheap. You get what you pay for. Wanna know why “An Inconvenient Truth,” didn’t have any net effect on the polls (and it didn’t — look at the Gallup Poll — if you think it did, you’re living in the environmental bubble)? They chose fast and cheap. They rushed it into production in the fall of 2005 in panicked response to the summer of 5 hurricanes.

They did not spend $10 million to hire the very best screenwriters in Hollywood to pull a month of all-nighters and come up with a powerfully structured story that mass audiences would be enraptured with and want to tell and retell for decades. No, they rushed a prominent speaker onto a stage to shoot three takes of the Powerpoint presentation he had been giving for a while. No fault of his. He was just trying to help. It was whoever made the decision for cheap and fast. And the science world for not having high enough communication standards to distance themselves immediately from such an effort. Oh, well.

You want to know how to make the topic of ocean acidification compete with the Kardashians? Choose fast, expensive and excellent. The environmental movement is overflowing with funding (just look at last year’s Climate Shift report), and the problem is going to be around for a long time. But if the approach continues to be fast and cheap, don’t expect anyone to take much interest. Until, of course, there’s a major crisis. And then it’s too late. Ho hum.

#224) ESA Session: Crowdsourcerers

August 14th, 2012

It’s fun to hate the masses, but sometimes they leave you amazed. The crowdsource/citizen science phenomenon can be powerful. I heard a few pretty cool examples last week in the session I took part in at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland.

IS THERE REALLY ANY BRAIN POWER IN THIS GROUP OF SCHMUCKS? Hate to admit it, but apparently yes.

space

CALLING ALL NON-EXPERTS

Who knew that average people, combined together, could be so smart and helpful? I saw a few impressive examples last week in the excellent symposium I took part in at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland titled, “Growing Pains: Taking Ecology into the 21st Century.”

First, there was Stephanie Hampton, of the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, who talked about how quickly the various local citizen science groups throughout the Gulf of Mexico last year were able to give a snapshot of the condition of seabirds following the Gulf oil spill. If you think back to 30 years ago when the government, with it’s limited resources, was THE source of such information, you can see how far we’ve come. There was no way the government agencies could have so quickly assessed the state of the seabirds across such a broad region. It was a case of the amateurs being more effective than the experts.

Then Alexandra Swanson of the University of Minnesota told about the rather stunning Serengeti Live project where volunteers get to analyze their photos for them. They have an array of 225 cameras set up in a grid on piece of the Serengeti snapping photos round the clock producing over a million images. Who has the time to analyze so much data? Volunteers, that’s who.

On their website people can volunteer to take on a stack of photos, looking at them for the presence of mammals (elephants, wildebeets, hyenas, etc.) and reporting what they see. They get a little bit of training first, then set to work, helping them plow through the superabundance of images.

Does this sort of “crowd-sourced” effort work? Is it reliable? Is it a bunch of amateur garbage?

maybe

AMATEUR IN, PROFESSIONAL OUT?

What’s happened in recent years, kind of starting with the realization that Wikipedia ends up being as accurate as Encyclopedia Brittanica, is that there is indeed great knowledge among the masses, where the individual limitations are overridden by the staggeringly large sample sizes.

If you want a great and dramatic demonstration of this, read the article in the July 9 issue of The New Yorker about TED conferences. The author uses a speaker on “crowd sourcing” as the central thread of the story. The speaker brings a live ox on stage during his talk, inviting web viewers to text in their guesses on the weight. At the end of the talk they present the average of the 500 guesses, which is 1,792 pounds. The actual weight is 1,795 pounds. Assuming we can believe that craziness (and given the recent feats of disgraced New Yorker writer Jonah Lehrer we should probably be cautious), that’s pretty crazy!

Lastly, I attended a biomedical symposium last year where I met Jamie Heywood, who gave a riveting talk about what has become his life’s work, creating a website called Patients Like Me (here’s his outstanding TED Talk on it). His brother died of Lou Gehrig’s disease (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis), but in the struggle to keep him alive, Jamie created a website for people with the disease which eventually morphed into Patients Like Me which now has over 150,000 people dealing with a wide range of illnesses. On the website the patients create their own personal profiles, sharing huge amounts of details about the medicines they are taking and the outcomes.

The result of the website is an enormous crowdsourced data base that in most cases far surpasses what doctors are capable of. For example, in the case of Multiple Sclerosis, they have over 20,000 patients. Which means if you have the disease and your doctor prescribes a drug, you can ask him how well it’s worked with the dozen or so patients he has who are taking it, or you can go to this website and look at the totaled, up to the minute results of the 20,000 people with MS who are sharing their knowledge on the drug.

The site is so powerful it ends up revealing enormous numbers of errors committed by doctors who simply don’t have the time or interest to keep up on the latest developments with various diseases and drugs. It’s amazing.

Bottom line, it is indeed a new era we have entered into. Or at least that’s what I heard was the finding of a recent poll of one thousand respondents, which means it must be true.

#223) Curiosity: Brilliant Filmmaking from … SCIENTISTS!!!

August 6th, 2012

Two historic things: landing of the Mars probe “Curiosity” and the production of a truly brilliant (especially now that the mission succeeded!) short video by a science institution, JPL.

space

space

DARE MIGHTY THINGS. You betcha. This video would be kinda hard to watch if the mission had failed. But it didn’t. And now it’s a thing of beauty. Complete beauty.

wow

HOW TO COMMUNICATE BRILLIANTLY: EQUALLY GOOD NARRATIVE AND VISUAL ELEMENTS

People ask me for examples of effective communication in the science world. Most stuff is terrible, but this one is truly amazing. It’s from JPL, which is maybe not such a surprise as they have had a long tradition of producing excellent visuals for their projects, but this one is more than just a bunch of cool visuals. It’s as good narratively as it is visually, which is rare.

I like web videos to be about 2 minutes in length. They need to be really good to justify much longer than that. This one is 5 minutes, and feels absolutely perfect.

It speaks for itself. Every element of production is wonderfully coordinated — the pacing of the editing, the graphics, the color palette, the close-ups of the scientists faces — even the sense of urgency in their “performances” — and they must be performances — the filmmakers must have coached them to have gotten such consistency in their tone.

And of course most powerful and effective (and important) of all is the music scoring — building an increasing sense of danger and tension.

Best of all is the finish, which is perfectly executed — like a triple body spin, flawlessly landed at the end of an Olympic gymnastic routine — they describe the last bit of the probe landing, finish on a shot of the rover on the martian surface, then exit with the challenge, “Dare Mighty Things.” Which they truly have. And succeeded.

This is a piece of filmmaking/communication at the same level of achievement as what the scientists have done in landing the probe.

It’s a role model for other science organizations. Judges Score: A perfect “10”. If we ever had a video like this submitted to our S Factor Panels we’d have nothing to say, we would just be humbled.

#222) Good Communicators Don’t Need Hope

July 26th, 2012

Communication is equal parts science and art. The science part has the potential to be easy. If you can figure out the rules, then you’re set. The problem is the other element — the art of communication. There’s no rules for that part of it which makes it difficult for literal-minded folks when they try to understand what makes for effective communication.

#221) Finished Baseline? Roger Bradbury speaks the truth about coral reefs in the NY Times

July 16th, 2012

“Hope versus the truth.” It’s a battle environmentalists are going to face increasingly in the future. What do you do when “people want hope” but the truth is, there is no hope. Coral reefs may be/probably are/definitely look to be doomed. Do the math for ocean acidification for starters… it’s grim. That’s what Roger Bradbury has done with a powerful and truthful NY Times OpEd, which of course has irked a lot of people who feel, “you have to give us hope.” Really? Even if there isn’t any?

What do you do when the patient shows no further vital signs? Do you cling on to the possibility of the heart restarting itself? Do you hold out hope for the one time in a million when a flat-lined brain springs back to life. Do you resort to mysticism and belief that the dead shall rise again? There are major elements of “facing death” going on right now for the coral reef community, with long time coral reef ecologist Roger Bradbury having the audacity to finally say, “Stick a fork in it.”

yum

YEE WHO SPEAKETH THE TRUTH

My old friend Roger Bradbury (he was a research scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences back when I was a postdoc there in the Pleistocene) has written a powerful and blunt OpEd in the NY Times (Andy Revkin has hosted a discussion of it on his Dot Earth blog) which I helped with a bit early on (we had dinner two months ago in Canberra when he was just getting going on it). There are two reasons why it is not just an important essay, but I think is one of the best pieces of environmental writing I’ve ever read (of course, I have little patience for most “environmental writing” that is nature adoration in a world of decline — this piece I love because it blasts out the truth).

It’s powerful first because it says coral reefs are doomed, and second, because it calls into question this dilemma of “hope versus truth.” He hits the second point on the head by stating, “conservationists apparently value hope over truth.” That is so beautifully and concisely said. Boom. There you go. The canary in your cage is dead — quit telling people it will do tricks if they’ll just give you money. It’s like a Monty Python sketch.

I’ve been dealing with this hope vs. truth dilemma for over a decade with my Shifting Baselines Ocean Media Project, so let me offer up here 5 perspectives that relate to what Roger has said.

hiho

1 “THANKS, GLAD TO KNOW GOOD PEOPLE ARE ON THE JOB”

In 2002 I produced a 5 minute Flash slide show titled, “Pristine?” that was the centerpiece of our Shifting Baselines campaign. In an early draft, after going through a lot of grim facts about the worldwide decline in fisheries, the narration then said, “But there is hope,” and told about a marine reserve in the Florida Keys where grouper were now getting larger. In showing the piece to various friends, a clear pattern emerged. Environmentalists (who were so demoralized) absolutely LOVED that last bit and thanked us for “giving them hope.,” but non-environmentalists — my knucklehead friends who knew nothing of the state of the oceans — they mostly had a consistent response of, “You had me all the way up until the grouper thing.” Meaning that all the bad news got them really upset and wanting to somehow get involved with the issue … until we told them that in the Florida Keys we’re already fixing the problem. Their feeling was, “oh, whew, that’s great, you’ve clearly got good people on the job and don’t need my limited time and effort — good luck to you, and please tell those folks in the Keys to keep up the good work!”

It’s very, very tough in today’s world to motivate anybody. These things are not simple or easy. So what do you want with your communications — something that motivates the unmotivated, or something that boosts the morale of the motivated? You can’t always have both. It’s NOT easy. I don’t have the answer, I only know that Bradbury’s essay brings this mess into focus. It’s something that environmental groups should be discussing. If you get too deep into deceiving the public about nature you will eventually lose their trust.

zomb

2 HAPPINESS FIREPOWER VS. ZOMBIE TRUTH

Do you have any idea how powerful the existing message in our world that “coral reefs are fine” is? I do. I saw it in 2005 when we thought about doing a Shifting Baselines project in the Florida Keys. At the invitation of a group of folks down there, I spent a week traveling the Keys talking with about 25 central characters in the ocean conservation scene trying to figure out if we could do something meaningful in terms of communication. What I learned was that they have something called the Florida Keys Tourism Development Council. I met with three of the nine Council members. They had (and probably still have) an annual budget of $10 million to blast out the message to the public that, “Our coral reefs are pristine and protected.” Seriously? What a pack of lies. The coral reefs of the Florida Keys are a ravaged mess with only a tiny fraction protected by poorly enforced regulations. I was told by sources they were using stock footage in their commercials of healthy coral reefs from the Bahamas and old photos for their brochures taken 25 years earlier before the reefs had died. Just a gigantic propaganda campaign to sell the reefs of the Keys. Why not? If I were one of them I’d probably do the same. It was (and probably still is) like a giant Match.com experience where the person’s photos look nothing like the person today. Selling the dream, not the reality.

So what are you going to put up against such massive communications firepower — a bunch of wimpy academics saying, “We think that possibly, maybe, sometimes, given the wrong conditions, in some places, there may be a few coral reefs that might be less than pristine”? No. You need a ball buster like Roger Bradbury to just shout it out to the world in the NY Times that coral reefs have become, “zombie ecosystems, neither dead nor truly alive.”

Mass communication is a tough game that doesn’t lend itself well to subtlety. The Florida Keys TDC doesn’t bother with nuance. What are you gonna do? It’s called the real world.

why

3 TECHNOFIXOLOGY (ESCAPE FROM TODAY’S REALITY)

Some of the coral reef folks speaking out against Roger’s OpEd point to the ability of some corals to adapt to warmer waters through heat-tolerant strains of their symbionts. Come on. Do you really want to be in the same boat with legendary climate skeptic Fred Singer? I interviewed him for my movie, “Sizzle: A Global Warming Comedy.” The guy wrote a very lame book titled, “Unstoppable Global Warming: Every 1500 Years,” which even one of the other climate skeptics in my movie dismissed off camera as rubbish. In his book he cited the work of my long time friend Mary Alice Coffroth on heat tolerance in coral symbionts, which really irked me. He was basically saying her small scale work showing a tiny bit of heat tolerance of a few species of corals is proof that entire coral communities will have no problem with massively, rapidly warmed oceans. We don’t know this at all, and this just becomes a means of escape from reality that is no better than gambling on as yet unforeseen aspects of technology that may or may not solve our future problems.

me

4 CONNECT THE DOTS

This is sort of Roger’s main argument — that we still have some reefs, and yes, if somehow the entire planet puts the brakes on the disastrous climate trends over night, that calamity will not befall coral reefs, but what are the odds of that happening? Not likely. All you have to do is connect the dots of today’s situation then extrapolate the curves, not that far, and coral reefs look doomed. End of story. No reason to expect anything different. Just look at the plot for coral reefs in the Caribbean that Jeremy Jackson referred to repeatedly in his excellent plenary talk last week at the International Coral Reef Symposium (where he was given the Darwin Medal — yay!). The curve for live coral cover in the Caribbean from the 1970’s to the present is a straight downhill trend, showing a net decline of between 50% and 75% of the coral. I know this trend too well. I dove the reefs of Jamaica’s north shore in 1978 when they were a coral wonderland. Now the entire region is mostly dead coral rubble covered with “slime” as Jeremy and others describe it. It’s grim and getting grimmer.

god

5 BALL-LESSNESS

I traded emails with a prominent climate blogger about Roger’s OpEd. He complained to me about the “ball-lessness” of the climate community. Same for the coral reef community, which is why Roger wrote such a loud, powerful, and impassioned piece. It’s a sort of cry against the fading of the light and I am 100% there with him on it. I’ve seen the decline in my lifetime. Dammit, people, what does it take to get large scale movement on this???

Ten years ago in Santa Monica we held a fascinating “Round Table Evening” for Shifting Baselines in which we assembled 100 concerned folks with a “round table” of a dozen experts including Jeremy Jackson to talk about the world’s ocean problems. One person gave an impassioned discourse on the need to “emphasize the positive” while avoiding “doom and gloom.” This was our first introduction to this struggle between hope and truth. He finished by very confidently saying, “People protect what they love.”

Yeah? Really? Bullshit. Sorry. I remember my buddy Katy Muzik giving an amazing talk at the 1985 International Coral Reef Symposium — waaaay before coral reef scientists realized their beloved resource had terminal problems. She told about the people of Okinawa, Japan who have all these rituals and ceremonies and parades filled with artwork of all their favorite sea creatures from the coral reef fish to the clams and lobsters and shrimp and … everything else that no longer could be found in their coastal waters because while they loved and respected all these lovely creatures, they had also eaten the holy crap out of them or destroyed them through careless coastal development. Their coral reefs, even in 1985, were shot. Her talk was heart wrenching, and for everyone present with a heart she brought out deep feelings. But for a few robot zombie scientists without hearts she ended up getting tongue lashed for presenting such a “non-scientific” bunch of hogwash. Well, it’s almost 30 years later. She was right, you were wrong, and that’s what Roger’s OpEd is about.

Furthermore, Jacques Cousteau did the ultimate, all time job of getting people to love the oceans. He was wonderful. But if you plotted the health of the oceans versus how much effort he exerted each year getting people to love the resource you could have your spurious correlation to suggest he caused the problems — the more he popularized the oceans, the worse they got, but there’s no relationship, only the proof that people can both love and destroy something at the same time. We all know the whalers loved and respected the whales they slaughtered.

So I’m pissed. That’s the bottom line. I loved coral reefs. EVERYONE who dived on coral reefs in the 1970’s knows what we’re talking about. They have been ravaged. The Emerald City, Pear Tree Bottoms, the Haystacks — these are just a few of the spectacular, legendary coral formations that existed on the north shore of Jamaica in the summer of 1978 that I spent at Discovery Bay Marine Lab. They are all gone, gone, gone. Not a trace remains. Literally, just like the dinosaurs. We saw them, you can’t.

This isn’t a case of “alarmism.” The alarms were already sounded, starting in the late 1980’s (actually starting even earlier with people like Katy). I remember Tom Goreau, Jr. in 1989 being one of the first to connect the dots on coral bleaching by assembling plots showing ocean temperatures and coral bleaching events. He got the same sort of ridicule for things which now are completely accepted. It’s tough watching science progress. It’s not a pretty picture. And now there is an ugly picture for coral reefs, which Roger Bradbury painted like a true realist this past weekend in the New York Times.

The truth hurts. It really does.

#220) THE “S” TEAM COMMUNICATION WORKSHOP: The Basic Concept

July 2nd, 2012

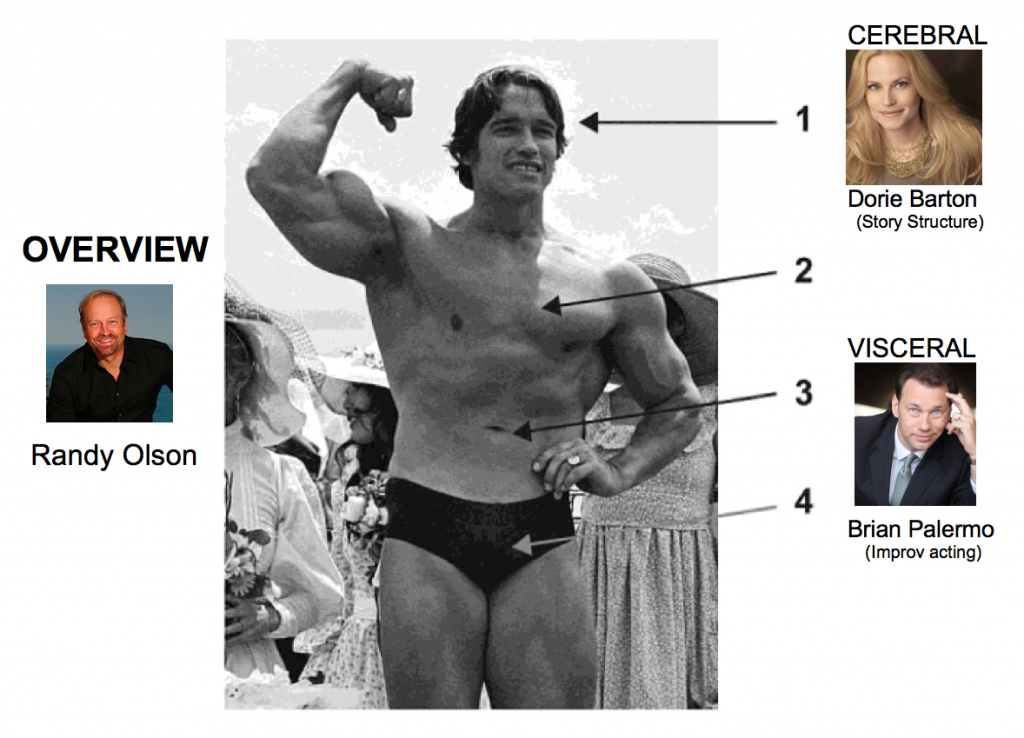

For the past year we’ve been developing “The S Factor Team” where we break down my basic approach to storytelling (as the central element to broad communication) into the “cerebral” (with screenwriter/script analyst/actress Dorie Barton) and the “visceral” (with improv instructor/actor Brian Palermo).

BREAKING DOWN “THE “S” TEAM.” For our workshops with science, public health, and environmental folks, I provide the overview of the cerebral vs. visceral elements of broad communication, much of which can be found in my book, “Don’t Be Such a Scientist.” I’m also somewhat of an “interpreter” for the more analytical folks being “bilingual” from having formerly been a tenured professor of biology then spent 20 years living in Hollywood attending film school, acting school and making films. Then I bring in two professionals (and long time friends) from Hollywood. Dorie gets deeper into the more cerebral elements of story structure using the foundations of narrative, based on her work in script development, while Brian brings in the energy of his career as a Groundling in Hollywood using improv acting techniques to come down out of your head and find the power of the more visceral forces. As actors they have both appeared in major films including, “Legally Blonde,” “Meet the Fockers,” “The Social Network,” and “Thank You for Smoking.” They are a real treat to work with.

scooby

COMMUNICATING THE WAY THE NOBEL LAUREATE TOLD US TO

A couple of weeks ago, I made some hay out of how Economics Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman told all the heavily cerebral types at the National Academy of Sciences‘ conference on “The Science of Science Communication,” that without creating a voice that is both likeable and trusted, all their evidence will never mean much. Likeability and trust are largely visceral forces. I found it to be a stunning message from one so cerebrally advanced, it’s also the core of my book and the workshops I run.

Over the past couple years I’ve gone further with this cerebral/visceral divide by assembling a team with a voice for each of the two elements. We began by doing workshops with the American Geophysical Union called “The S Factor”, so I figured we might as well use the same “S” name for the team.

I began assembling the team last year with an all-day workshop in Los Angeles for 25 environmentalists. I’ve known Dorie Barton for about a decade — first as an actress, then as script analyst for a friend’s company where she quickly became their most trusted voice for whether a script “worked” and if not, how to fix it. Brian Palermo I met through the Groudlings Improv Comedy Theater, cast him in a short film, then realized at the LA workshop he’s a tremendous improv instructor with the kind of energy that makes a workshop catch fire.

In February of this year we did our “S Factor” thing at the Ocean Sciences meeting. Next month we’ll be doing another all day workshop in San Francisco, this time with one of the largest environmental groups in the country.

At the core of the workshop is one concept — storytelling. The thing about storytelling is nobody’s perfect at it, it takes a long time to get both the cerebral (story structure) and visceral (character development) sides of it, and even the most successful storytellers in Hollywood still produce the occasional stinker that makes you wonder whether they really know much of anything at all (I remember when I first moved to Hollywood in 1994 hearing the industry buzz on Rob Reiner that, “he’s never had a flop,” then a friend took me with her to the premiere of “North” and there was Mr. Reiner walking around looking depressed — it has 11% on Rotten Tomatoes, stinky poo-poo!).

The best thing about storytelling is that when it works, it works so powerfully. As I was saying last week about the Aspen Environment Forum. It’s at the core of almost all effective communication, which is why it’s at the core or our workshops.