#3) STORYTELLING: The Power of Specifics

January 11th, 2010

I’ve come to the conclusion that storytelling is the single most important dynamic in mass communication. A few years from now I may change this opinion. I can’t offer any guarantees. I can only say that at this point in my journey, having gone from the world of science to the world of cinema, storytelling is what now stands out to me as the most important element. Why? You can begin with the fact that about 85 percent of the world gets their beliefs through stories. Try listening to this very compelling recent segment titled, “God’s Green Earth,” about the importance of the religious masses in addressing the environmental future — he talks about storytelling. We can also look to Joseph Campbell, who late in life captured the ears and minds of the intelligentsia with his persuasive arguments about the universality of storytelling through the ages. And think about the greatest talks you’ve ever heard — most of them were probably well told stories.

“HIS STORIES WERE SO SPECIFIC”

I remember reading long, long ago one of Joseph Wambaugh‘s early non-fiction crime books about a serial killer around Philadelphia. The man had managed to assume several false identities and did an impressive job of deceiving people. The thing that Wambaugh mentioned repeatedly throughout the book was that the most common comment from the people who were taken in by the killer’s deceptions was that “his stories were so specific.” Some of them sensed that overall, the stories he told of who he was and where he had been didn’t seem to add up, and yet … the amount of detail he was able to provide when he claimed to be a famous architect — he knew the names and catch phrases of the most popular current architects — or a train conductor — he knew the load bearings of the various types of rail gauges — on and on. What mesmerized the people was the specifics of his stories.

The power of good storytelling rests in the specifics.

This is yet another fundamental, simple rule they ground into our heads, not just in film school but even more so in acting class. It’s extremely important and is something that takes extra effort and so doesn’t always come naturally. Lazy people slip into vague generalities and platitudes. To cite the specifics takes extra effort.

Once you begin to absorb this principle, you see it has a great many ramifications. For starters, isn’t this what good science is about? “Cite your sources and data!” Don’t tell us general statements about how you think a certain enzyme works. We want you to tell us the exact studies and show us the data so that we can add it all up and draw our own conclusion. The power is in the specifics.

But here’s a bigger and more important explanation of what I’m saying that comes in the form of one of the very best articles I’ve ever read on this elusive question of “How do we communicate our message?”

A GREAT AND IMPORTANT ARTICLE: “NICHOLAS KRISTOF’S ADVICE FOR SAVING THE WORLD”

So let me get specific here. Last month in Outside Magazine Nicholas Kristof wrote a great, great article titled, “Nicholas Kristof’s Advice for Saving the World.” Now that I think of it, that’s actually kind of a lame title. Sounds a bit like they’re trying to parody something like “A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” (I’m guessing some editor rewrote whatever title he initially had on it). But in fact it is SUCH a good article. He is a prominent writer for the New York Times and has many years of experience reporting in Africa which he draws on for the article.

He presents two major points:

1) HOPEFULNESS – this has become one of the ubiquitous principles of environmental communication — that you have to give people hope. What’s good about Kristof’s article is he breaks it down analytically in terms of how the hope stuff works. If you pick a target group of people to help and tell your donors that their effort will help 3/4 of the group, they will feel hopeful that what they do really matters and will join in. But if you present numbers showing their donation will only help 1% of the starving, writhing masses, they’re just going to say, “Well, that’s hopeless, I don’t want to waste my time.” He explains it very well.

2) SPECIFICS – to me this is the better and more novel part of what he has to say, and which connects with the theme of this essay. Here’s a quote from his article:

As we all vaguely know, one death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. As Mother Teresa said, “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”

THE HOPELESSNESS OF TRYING TO USE BIG NUMBERS TO COMMUNICATE GLOBAL WARMING

This is such a powerful and important aspect of communication, and its the part that is MOST relevant to scientists. Think about what he is saying, then think about all the global warming literature you’ve read that says, “We’re producing fifty jillion tons of emissions that are going to cause the death of eighty gajillion people if we don’t stop.” Are there really folks who think that lights a fire inside someone? Obviously there are, and this is what Kristof is pointing out with his article — that too many “Save the Starving Africans” projects have failed to grasp the impotence of such messaging.

You have to bring it down to the specifics and find “the human face” of the issue you’re addressing in order to really get people to relate. And that was one of the many problems with the movie “An Inconvenient Truth” — the only face they managed to find for the issue of global warming was that of an affluent, white, male, elderly failed partisan politician who talked in big, vague numbers. Somebody forgot to listen to Mother Teresa.

I will harp further on this theme in subsequent essays. Kristof really nailed it. It’s about the specifics, and he even used his specific experiences in Africa to further bring the point to life.

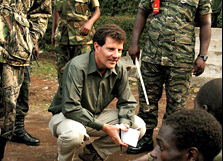

And by the way, on a tangential note, one of the saddest and most disillusioning documentaries I’ve ever watched was, “The Devil Came on Horseback,” which is the story of a young former military guy who was hired as a photographer in Darfur and ended up with photos the world had never seen about the brutality of what was occurring. He came back to the U.S. thinking that the media world would be all over his photos and their publication would cause an eruption in the political world, but instead what he found was a basic lack of interest, a disconnect with the topic, and lack of desire to get involved. But guess who the one guy was that saw the power of what he had captured in those SPECIFIC images and ended up getting them published for him in the New York Times — Nicholas Kristof.