#1) THE BENSHI BEGINS…The Evolving World Of Science: What We Can Learn From Our Critics

January 4th, 2010

Happy New Year and welcome to this new “on-line journal” which will be a collection of essays. It will be sort of a continuation of thoughts from my book, “Don’t Be Such a Scientist: Talking Substance in an Age of Style.” In the essays, which will be roughly twice a week, I will be making reference to parts of the book from time to time.

The book is reviewed this week in Science and last month in Nature. In both cases they paired it with Cory Dean’s, “Am I Making Myself Clear,” which is not only an honor to be in her company (she of the NY Times Science Section), it’s also a great combo because the two books fit together well. Her book is more of a practical guide in communicating science to the public, mine is more conceptual — sort of like “ways to align your brain before you even start thinking about what you’re going to say.”

Both reviews are positive, but there are things that Peter Kareiva said in his review in Science that are so important and well stated they actually go substantially beyond the book. I’m going to explore a few of them in the first few essays I write here, so let me start with the idea of addressing critics of the book (or actually NOT addressing critics), and his comment along those lines.

THE CRITICS ARE NEVER WRONG

One of the really good things they ground into our heads in film school is that criticism is important and it’s never wrong. It’s highly subjective. It’s people’s opinions. And opinions simply are what they are. The best thing you can hope to do is ignore a critique if you don’t think it’s helpful, but hopefully you’re at least able to hear it.

But one thing they didn’t tell us about with regard to criticism is the idea of searching for patterns in the critiques that can tell us more about the subject you are exploring. I did this last year with my movie “Sizzle: A Global Warming Comedy,” and now I’m finding myself doing it with the responses to the book.

For “Sizzle,” there was a loud and cantankerous response among scientists and heavily analytical types. I experienced this first from my scientist friends who saw early cuts of the movie, then from a group of senior scientists who viewed it at a science meeting, and then finally from science bloggers who reviewed the movie prior to it’s premiere in July, 2008 at the Outfest Gay and Lesbian Film Festival. Their responses to the film were markedly different from what the non-science/non-technical audience had to say about it. The latter simply enjoyed the film, the former found it annoying, boring, offensive, hard to follow, vacuous, and lots of other wonderful things (and they’re probably pissed to see the poster in Science this week as the illustration for the review).

When I gathered together all the feedback and began parsing this pattern out of it, the science crowd got doubly angry, accusing me of being “defensive” and “thin skinned.” In the book I tried to explain to them that their critiques were gentle compared to the batterings I’ve endured in Hollywood. I finally encapsulated it all with an appendix in the book titled, “The Sizzle Frazzle.”

Now I’m seeing a similar dynamic in the responses to the book. In general all the reviews are very positive and we’re having a great time with it. And as I said, I don’t begrudge anyone their opinions, in part because I agree with most of the critical statements — there’s always so much more you could do with any project.

BUT CRITICS CAN PROVIDE “TEACHABLE MOMENTS”

It’s a bit like what our fearless leader, President Obama, advocates in terms of “teachable moments.” There’s a difference between trying to wrestle your critics to the ground in a head lock versus asking the question, “What can we learn from the way people are responding to this piece of media?”

So the starting point for this examination is provided by Kareiva’s review in Science when he says, “Some readers will find Olson’s autobiographic treatise off-putting and a bit narcissistic. But to be turned off by Olson’s style only proves his point.”

I could not have put it any better. As I said, most all of the reviews have been good and the emails I read from people basically saying, “I get it!” in response to the book are really nice. But there are a number of science bloggers and even Amazon Reader Reviews who have referred to the book as an “autobiography.” There is MUCH to be said about this.

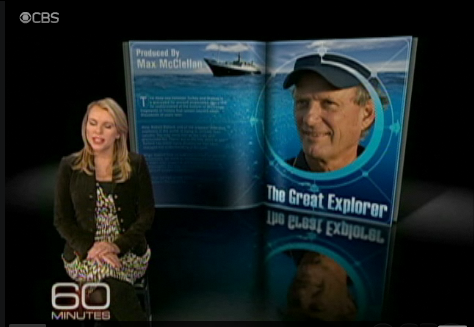

BOB BALLARD NAILS “THE I/WE DILEMMA” ON 60 MINUTES

The breathy Lara Logan hosted an excellent "60 Minutes" segment on Bob Ballard in which he went to the heart of how the profession of science diverges from America's star-based system.

Let’s begin with the WONDERFUL interview that 60 Minutes did a few weeks ago with geologist/ocean explorer Bob Ballard. I’ve never met him, never had a clear opinion of him, but I have to say he really nailed the fundamental social dilemma of the science world. The news show 60 Minutes did an amazingly detailed double segment on him, hosted by the breathy bombshell Lara Logan.

Ms. Logan was hinting to Ballard that he is at times “more of a salesperson than a scientist,” to which he immediately agreed. Here’s the transcript of what is said after this:

He also acknowledged it doesn’t hurt to be known as the guy who found the Titanic, but he said that comes with baggage. “Science is a ‘we,’ not an ‘I.’ It truly is. I didn’t do anything. We did a lot of things. But in our system, in America, we have this star-based system. Star athletes, star news people, star politicians. And stars are ‘I.’ And the academic world is really, honestly a ‘we.'”

“But you’re the star quarterback,” Logan said.

“I’m the star. But it can get you in trouble in that world that doesn’t believe in that star-based system,” Ballard said.

Oh my goodness. Has anyone ever stated it as clearly as this on national television? Thank you, Bob Ballard. This is part of the fundamental dilemma. And I think it’s something that the science bloggers are tearing themselves to pieces over these days.

Blogging is not much of a “we” exercise. There are a few good folks, like the RealClimate.org team, who have managed to wrestle the format into that convention. But for the most part, it is very much an “I” exercise, and the louder the “I”, the bigger the audience, with the splendidly vocal and amusing P.Z. Myers taking first place for largest audience for a scientist in the blogosphere. Many people have complained about the cult of personality that arises around blogs like P.Z. Myers’ Pharyngula. But as Ballard would probably say, welcome to America, where everybody loves a star.

And the bigger, more central issue at work here is storytelling and the narrative voice. People seek out good storytellers. Storytellers become popular based on several central traits. One of those traits is a clear and confident voice. Nobody wants to listen to a shrinking violet who is not certain of what he or she is saying. Telling stories that say, “this is what maybe happened, or maybe it was this …” doesn’t win you a crowd. Coming on loud and confident does (i.e. “the salesman” that Logan was accusing Ballard of being).

As Ballard says, the science world evolved it’s own different way of doing things, built around the concept of “we.” This is so true of scientists. It manifests itself with the basic feelings of resentment of people who take lead roles, and the sort of “who does that guy think he is,” type of sentiments when a scientist slips into the “I” mode of speaking.

DUDE, YOUR AUTOBIOGRAPHY SUCKS

Twenty years ago I (excuse me for a minute here while I indulge in some “I speak”) began my journey into the media world by writing a book manuscript about all my crazy years of living in Australia conducting research on the Great Barrier Reef. I was a mere thirty three years old when I wrote it. E.O. Wilson (a former mentor in grad school) read it, called it a “picaresque tale,” and told me it made him wish he had written his autobiography when had been my age rather than waiting until his late fifties when “the fire in my belly had gone out.”

Despite several literary agents and editors it never got published largely because their attitude was, “Come back when you’ve won a Nobel Prize and people want to listen to you.” But I was at a party at a scientific meeting in 1993, the last one before I moved to Hollywood, and a tipsy jackass scientist colleague said to me, “Hey, I heard you wrote your autobiography — that must have been a challenge since I never knew you did anything interesting?”

The problem with both his comment about that book manuscript, and the recent comments about my book, are that neither pieces of work are “autobiographies.” Autobiography is “a book about the life of a person, written by that person.” Neither books have been about “my life.” Neither book told anything about my childhood, nor presented the narrative journey of “my life.” The first one was an exercise in showing how much fun it is to do field work in marine biology. The second one is what I learned about communicating science to broad audiences by moving to Hollywood and getting involved in making films.

THE WORLD OF SCIENCE IS DOING THIS THING CALLED “EVOLVING”

And so here’s where we can now see the patterns in the feedback. No one from the non-science world says ANYTHING disparaging about the book being “an autobiography,” or an exercise in self-indulgence. To the contrary, the non-science audience appreciates the personal stories. They appreciate them because the stories are ALL functional. This is an agreement the editor, Todd Baldwin, and I made from the outset — that no stories would go into the book unless they were serving to illustrate the principles being presented. Plain and simple. It was a rule we stuck to.

Which makes it almost baffling when you start reading the responses of scientists disparaging the book as “an autobiography,” and, exactly as Kareiva said in his review, calling it narcissistic. And by the way, if it was an exercise in narcissism I certainly wouldn’t have shared the countless humiliating stories of me being laughed at in Hollywood.

The bottom line is that, as I said towards the end of the book, the world of science is changing. Big time. And along with these changes are some major identity problems. Such as these science bloggers who are caught in the divide between the “I” and the “we” that Ballard spoke of. They have been trained to be “we” folks, but they are realizing that to achieve popularity with your blog, you kinda gotta move in the “I” direction. And that must be uncomfortable for many of them.

No telling what the solution is for this. The science world is changing. Change is perhaps the most difficult thing for humans to understand. In fact, it’s so complicated and complex the world of science developed an entire discipline dedicated to the study of change. It’s called evolution.