356) Are Inventors Better Listeners?

July 2nd, 2014

Scientists may not be the best at listening, but what about when they are inventors? I had a mind-altering experience yesterday with the AAAS-Lemelson Invention Ambassadors, leading me to connect the dots with what improv teaches.

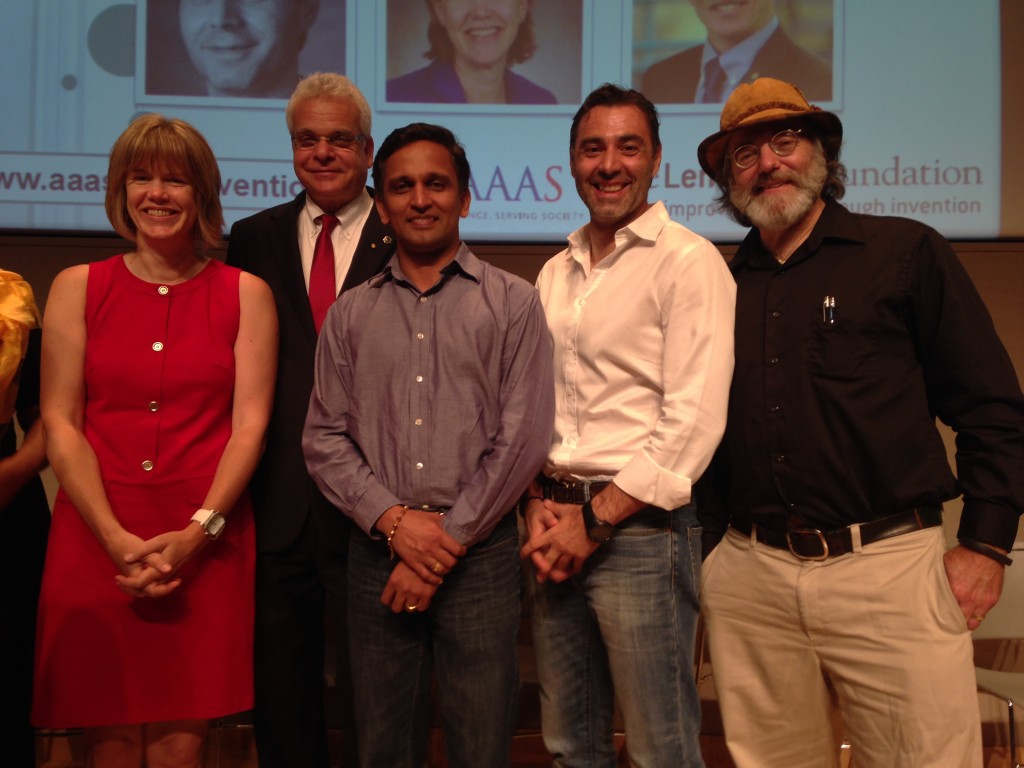

THE AAAS-Lemelson INVENTION AMBASSADORS. Among many amazing attributes, they appear to be role models for the ability to listen. From left: Karen Burg, Paul Sanberg, Vinod Veedu, Sorin Grama, Paul Stamets.

LISTEN, DO YOU WANT TO KNOW A SECRET?

In reviewing my first book in Science, Peter Kareiva, the Chief Scientist of the Nature Conservancy noted that the one thing I failed to address adequately is scientists’ inability “to listen.” It was a valid point that made me wish I had added one more chapter titled, “Don’t Be Such a Poor Listener.”

In the years since its publication I’ve had countless experiences that have made me flash back to that comment and think, “He’s so right.” And of course the reason my crazy acting teacher screamed at me the first night of acting class (which was the opening scene of my book) was exactly that — she knew that heavily educated people have a hard time listening.

But yesterday I had my head spun around by the group of five Invention Ambassadors assembled by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Actually, the head spinning began two weeks ago when I started a series of phone calls with each of them, listening to what they planned on presenting in their 12 minute talks to the public (I was brought in by the AAAS folks to work with them on their presentations).

I went to work with them searching for good stories in the “moments of discovery” that I knew they all must have experienced. Sure enough, each one had a single great moment to relate that included a moment of collaboration, a moment of pulling a discovery out of the ashes of failure, a moment of breaking the boredom with a discovery, a moment of using a daughter’s Barbie Doll dish to take care of a carpenter ant problem with mycelia, and a moment of realizing there are large numbers of inventors at universities who suffer the same perception problems of the academic world not appreciating their efforts. Five great stories.

But the thing that stunned me was their ability to listen. I had feared I might have a group of people saying, “Look, we’ve given lots of talks, we don’t need your input.” I mean seriously, one of them had given a TED Talk that has scored over 2 million views. Why wouldn’t they tell me to get lost? But they didn’t.

THE MAGIC OF LISTENING

They listened. They experimented. They pushed my suggestions further. And they ended up giving really great talks that will be posted soon.

I think what was most important was what they didn’t do—they didn’t negate. They basically took every suggestion with the same sort of, “Yes, and …” approach that is the centerpiece of improv training.

I don’t think this is a coincidence. The ability to listen like this is not something that people pick up overnight. It’s a long term process. I see it with improv instructor Brian Palermo. He is unlike anyone I’ve ever collaborated with. He’s really great to give notes to because he is so deeply trained, with his 20 years of improv experience, in how to listen.

It’s a crucial resource. This Invention Ambassadors program is a new thing for AAAS. They are just now figuring out how to make best use of them in the upcoming year. I think one thing they should have them talk to the science community about is how they all seem to have developed this exceptional ability to listen. There are lots of very impressive things about these five individuals, but to me, this is one of the things I really wasn’t expecting. And again, I’m certain it’s not a coincidence. Great ideas come from people who know how to listen.