#116) “Science Home Movies”

February 24th, 2011

Home movies. Parents make them. Neighbors hate them. Why? How could everyone not love something that someone is so passionate about? The time has come to talk about the concept of “Science Home Movies.” Same for environmental ones as well.

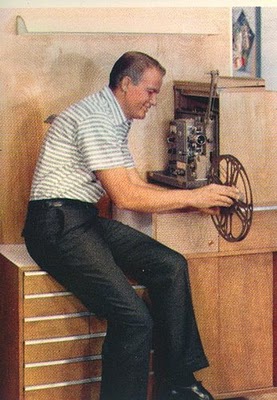

HOME MOVIES. Here’s Dad with his movie projector. He’s getting ready to show movies of the kids on vacation, at the park, riding their bicycles, splashing in the pool. His neighbors are coming over for the evening. They don’t know that after dinner Dad will be pulling out the projector. Dad is sooo passionate about his kids. Surely the neighbors will love the movies as much as he does. Maybe he’ll also talk about his scientific research on bopyrid isopods. He’s passionate about that, too.

REJECTED

Once upon a time, long, long ago I wrote my very first popular article for a magazine about the natural history of the sea squirts I studied for my Ph.D. But the editors rejected it. I was heart broken. I loved those amorphous little blobs living on the sea floor. How could the editors not sense my passion and not want to share my passion with the world so that I could make them passionate about my blobs, too?

Had the editors been cruel enough they really should have said to me, “Your article is about as interesting as watching our neighbors’ home movies of their kids on vacation.”

It dawned on me recently that this is an apt term for a lot of science and environmental communication. I don’t want to go through the specifics, but I have a list of a dozen environmental documentaries released since “An Inconvenient Truth” that fit this label. They’ve all either lost a lot of money for the filmmakers by drawing trivial audiences at the box office, or they’ve gotten lousy reviews that sadly point to the good hearts of the filmmakers, but the overall boringness.

NOBLE INTENTIONS COUNT FOR NADA

For one of the environmental movies Roger Ebert said, “Despite it’s noble intentions, this movie is a bore.” For another, the reviewer from Variety said, “Well-intended and informative, but also unfocused, unwieldy, and a little smug.” The operative word is “intentions.” They count for nothing in real life. Not even in horseshoes and hand grenades.

These movies failed to reach the elusive broad audience that every environmental warrior so desperately yearns for. Why is this?

You can attribute it to “Home Movie Syndrome,” which I would define as the tendency to be so blindly passionate about your topic that you sadly assume the rest of the world shares your passion. And you also tend to assume that passion alone is enough to motivate the public to both watch and enjoy your movie (or book or talk or website).

Where does this “home movie” term originate? In the 1950’s Kodak and other companies began making the first consumer level movie cameras which mostly shot 8 millimeter film. We used these old cameras for my first semester of film school at U.S.C. They were great.

No sooner did the cameras become available in the 1950’s than every mom and pop ran out, got one, began shooting mountains of film of their kids at the park, in the backyard, riding their first bicycle, playing in the dirt, then invited their neighbors over to watch the raw, unedited films.

By the time I was a kid the term “home movies” was a standing joke on TV shows like “Leave it to Beaver,” and “My Three Sons.” And at the core of it was this basic dynamic of the person who was “telling the story” (when in fact there was almost never any sort of structured story to begin with) being so wildly passionate about the subject matter (“Just LOOK at my WONDERFUL kids! Aren’t they hilarious and cute!”) that they would, with almost autistic indifference, subject their neighbors to hours of torture in their living room in front of their pull-up movie screen.

DEEP SEA HOME MOVIES

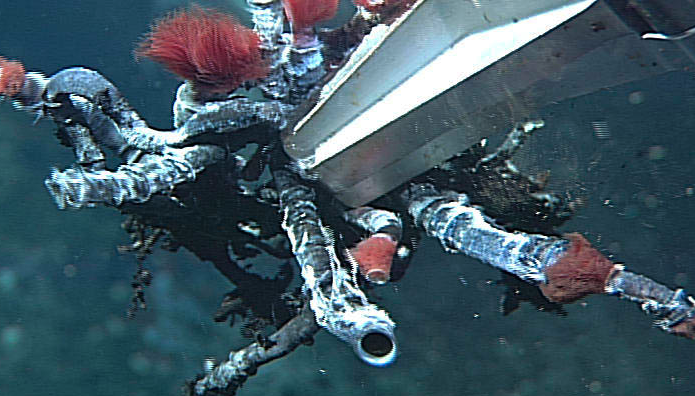

When I was in graduate school we got our own special science version of “home movies” in the late 70’s when the deep sea hydrothermal vents were first discovered off the Galapagos Islands. One of my thesis committee members, the late Dr. Ruth Tuner (bless her wonderful heart — in the near future we’re going to post the video I did with her and two other women scientists in 1992) would give seminars about the dazzling vestimentiferan worms discovered at these sites. She would show unedited video footage of the worms, which was incredible. For the first five minutes. But then …

DEEP SEA HOME MOVIES. “NARRATOR: The arm of Alvin reaches for the worms, closes on them, misses them, moves back, then left, then forward again, prepares to grab worms, closes the claw, misses the worms, pulls back, moves further to the left, prepares to grab worms …” Zzzzzz …

She would show these unedited video tapes of the mechanical arm of the deep sea submersible R.V. Alvin reaching out towards the worms, moving to the left, reaching further, trying to grab a worm, clamping down on it, missing it, pulling back, moving back to the right, reaching for another worm, missing it, pulling back … on and on as everyone in the room sat patiently silent. Watching. Listening. Hearing the faint sounds of someone snoring in the back of the room.

Undersea home movies. It’s a problem. Especially in today’s rapid fire Youtube world.

STORYTELLING TO THE RESCUE

So what’s the solution to Home Movie Syndrome? Storytelling. But more importantly, clearly STRUCTURED stories that follow a well-designed three act template. And this begins by having a thorough grasp of what the word “story” really means. At one scientific institution where I spoke last year, the communicators informed me that the scientists were constantly telling them, “We want you to ‘TELL THE STORY’ of our institution.” But when the communicators would ask them, “What is the story?” All they would do is itemize a bunch of facts.

Facts alone are not a story. Facts alone are the makings of a home movie. It takes more than just facts to tell a good story. This is something that Dad with his home movie camera never quite grasped. Which was okay for him. But it has DEFINITELY hurt the environmental movement of today.

NO MORE ENVIRONMENTAL MOVIES

How do I know this? Because when I spoke with distributors in 2008 about my movie, “Sizzle: A Global Warming Comedy,” they said to me, verbatim, there is no market for environmental movies. The public finds them dull, preachy, humorless and lacking good stories. And more recently a TV documentary producer told me, “Green is dead on TV — even The Green Channel doesn’t want green shows.”

Sorry if this breaks anyone’s heart. It shouldn’t have happened. You can partially thank PBS for setting the wheels in motion in the late 80’s with their, “Race to Save the Planet,” series which was a classic set of environmental science home movies. Environmental filmmakers should have made so many movies with such good stories that “the brand” by itself would be popular today. But they didn’t. They screwed the pooch. And all that remains now are lots and lots of science and environmental home movies.