#54) THE SHELF LIFE OF FILMS: A tribute to the honesty of three Maine lobster fishermen in 1991

July 19th, 2010

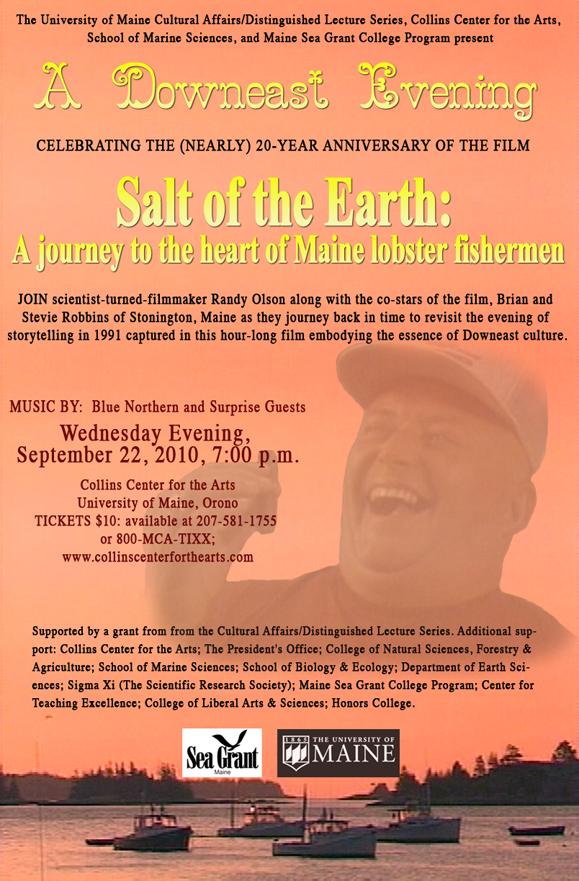

Nearly two decades after filming our simple, silly, and sentimental evening with three lobster fishermen from Stonington, Maine, we’re going to have a special screening of the film, September 22 at the Collins Art Center on the campus of the University of Maine, Orono. It’s not a well made film. I know. I made it. But it has something at it’s core that makes it every bit as watchable and enjoyable today as it was in 1991 when we completed it — it has the heart and soul of three lobster fishermen. And that’s all it takes to make something ageless — the human element.

TWENTY YEARS LATER: Veteran lobster fishermen Brian and Stevie Robbins of Stonington, Maine will be on hand to view the film we did with them nearly 20 years ago. It was a magical night of storytelling that we managed to record. It will be a memorable evening.

OUR THROW-AWAY SOCIETY

Some things last. Most things don’t. I keep thinking that, as we make plans for what’s going to be a great and memorable evening at the University of Maine on September 22 where we will present my film of three lobster fishermen which is now almost 20 years old. What makes this film worth watching so many years later? Why haven’t we just thrown it away?

In June of 1991 my crew of four and I traveled up the coast of Maine to the little port of Stonington to spend an evening with the Robbins brothers and their father in Stevie’s fishing shack. Before that, I didn’t know them and they didn’t know me. It all changed in one evening.

They had agreed to do an in-depth “interview” (more of a storytelling session) with me not because I was such a talented filmmaker, but rather because they believed I was NOT any good as a filmmaker. They told me this later. There was no way they would have EVER sat down with a bunch of professionals from PBS or Discovery Channel hoping to “capture the Downeast thing” on film. That would have been too exploitative for them. As I tell at the start of the film, I gave them a copy of my ONLY film at the time, the 5 minute short, “Lobstahs,” which a few months earlier had been panned as “decidedly lame” at the New England Film and Video Festival. A week later they watched it. Brian called me and said it was so bad they figured I had to be harmless. They agreed to meet and eventually opened themselves up to us in a manner that is rarely, if ever, seen in the quiet, reclusive lifestyle of working class folks in Downeast Maine.

The result is a film that’s worth watching, nearly two decades later. And as we gear up for this event, I find myself wondering, what is it about the film that justifies pulling together several hundred people for an evening, and why don’t I feel like it was just a product that served its purpose and lived it’s life? Why isn’t the film part of our throw-away society?

THE TRAGEDY OF “ONE SHOT” THINKING

The concept of “throw away” is linked to the idea of giving things just a single shot — sort of like “single use plastics” — like a plastic fork or cup. I learned this “one shot” approach to life by hanging around Hollywood for the past two decades. I never saw it in the academic science world before moving here, but I was eventually stunned to see that by the late 1990’s it had infiltrated the environmental world. Let me tell you how.

In 2001 I reconnected with my former marine biology colleague Dr. Jeremy Jackson to create the Shifting Baselines Ocean Media Project. I knew very little of the ocean conservation world. My life until then had consisted of twenty years of academic science, followed by six years of film school and seeking employment in Hollywood. Jeremy didn’t have much background either in the (unbeknownst to us) competitive world of saving the oceans. We thought it was as simple as good intentions and good ideas. We were naive.

As we set off on our mission to use my newly acquired filmmaking skills to help him communicate his conservation ideas to a broader audience, we were about to learn a great deal in a short period of time. The first thing we were told, from several communications directors for large environmental groups in Washington D.C., as well as more than one communications consultant, was that, “YOU ARE ONLY GOING TO GET ONE SHOT WITH YOUR IDEA.” I knew this concept from my years in Hollywood where this really does exist in terms of the way that big budget screenplays are sold. But I had never dreamed the same sort of thinking might have infiltrated the saintly world of saving the planet.

THE HOLLYWOOD ONE SHOT — MY ACTION SCRIPT

Here’s how the big budget screenwriting world works in Hollywood. You write a screenplay which you keep under tight wraps. Then you seek out an agent who will ONLY look at your script if you can assure the agent that no one — absolutely no one — in the entertainment business has ever even seen the title of your screenplay, much less read it. If the agent believes you on that point, and if the agent thinks you’ve got a decent title and pitch (something like, “It’s ‘Die Hard’ at a dinner table — a sort of action-version of ‘My Dinner with Andre’“), then no matter how poorly written the script might be, you’ll probably get a shot at a “spec sale” — meaning selling the script on speculation, ideally by creating a bidding war among production companies.

In 2000 I had a team of agents representing me as a writer at one of the top three agencies. They took one of my big budget action scripts and did exactly this. They staged a spec sale release of the script. It went out to roughly 75 production companies on a Tuesday morning. By the afternoon, internet message boards were ablaze with gossip about the script — “Anybody read this?” “Any bids?” “Anybody taking it to a studio?” By Wednesday morning there was “solid interest” from numerous companies and rumors that two production companies had “taken it to a studio” (which means that all of the dozens of small production companies have deals with the five or so big studios and are allowed a few times a year to bring them scripts they think are worthy. But they can do this only a few times, which means they have to be careful which scripts they choose to burn up those shots with). So it was a big deal they were choosing my script.

And yet. By Thursday the script was dead. Everyone passed. Lots of reasons. No need to go into them. But everyone liked the writing of the script and most said back to the agent, “We want to meet the writer.” Which left me with the worst case scenario — no money, but literally about 50 meetings to do. I did about 30. It’s what Hollywood loves to do. Take energetic people and grind them down through endless meetings.

But the main point of telling this is that in Hollywood, with it’s ruthlessly short attention span (and absence of social, political, or moral agenda other than making boatloads of money), ideas really are given only a flickering nanosecond of opportunity. And then? It’s the one word that best describes the working mentality of all Hollywood … “Next!”

And by the way, the reason I dreaded doing all those meetings was I had already done it in 1996 when my USC musical comedy short film was a big hit at the Telluride Film Festival. I did close to 100 meetings back then with producers, managers, agents, and other folks. Actually, I should clarify that — most of them were with the ASSISTANTS of the big shots. And guess what — similar to the short attention span on screenplays, most of the jobs in Hollywood turn over incredibly — blindingly — quickly. So much that by 2001 there was virtually no one from those 1996 meetings who was still in the same job or even with the same company. That’s how Hollywood is — constantly in motion, no long term agenda, except making money.

SAVING NATURE WITH A SHORT ATTENTION SPAN?

So then it was 2002. Jeremy was pulling me back into the world of marine biology. We were talking with all these ocean conservation people and I was hearing the exact same thinking I had gotten used to hearing in Hollywood. We were told, “The American public has the attention span of a gnat. If you come up with an idea for a conservation campaign, you need to realize that you’re only going to get ONE SHOT at the public. If your idea isn’t super duper blazing white hot such that it explodes into everybody’s heads and causes them to drop whatever they’re doing and restart their entire lives … well, then, you’ll be finished before you can even start.”

I’m serious. I heard this, over and over again. It was apparently being taught at media workshops that these communications people were attending. And of course we were in the midst of shaping our concept of “Shifting Baselines” as a mass media campaign, so according to them, our brilliant idea would only get ONE SHOT!

A lot of the details of this I reviewed in my book — about the “experts” telling us the term would be a disaster with the public as it sounded “too technical” to them. They basically said don’t do it, and if you are foolish enough to do it, be prepared for “the backlash” you’ll get after you’ve launched your campaign and it’s failed. At that point, nobody will want to hear even the sound of your title — you’ll be as useless as a day old newspaper.

I kept wondering, and even saying to some of them, “Yeah, but what if it’s actually an important concept that you’ve built your ‘campaign’ around, and you’re willing to sing a song about it that you’ll keep singing for the rest of time until you’re dead?” That seemed to be beyond their comprehension — as in, “Why would you want to start a new year with the same theme as the previous year?”

REVOLVING EMPLOYEES

We launched Shifting Baselines in the fall of 2002. It’s 8 years later. We’re still running it. It never “erupted” as a concept. It’s just been on a steady, slow build, year after year, as more people see the relevance of the term. So it’s still around, but virtually none of those people with their sage advice are.

Of the dozen or so Communications Directors I met in 2002, mostly with the major environmental groups based in Washington D.C., only one of them is still in the same job — Matt McClain, the guy who has been a driving force in making Surfrider Foundation one of the most powerful and effective grassroots environmental organizations ever. He is still their Communications Director, as Surfrider remains on course, year after year, with same key players — Chad Nelson, Michelle Kramer, Ed Mazarella, Mark Rauscher, Nancy Hastings, Joe Geever … on and on. Little wonder they are so effective. It’s called staying power.

All the rest of the Communications Directors, JUST LIKE HOLLYWOOD, had moved on to other organizations — other jobs within a couple years. I really couldn’t believe it.

SO THEN, WHAT, IN THIS SADLY MIXED UP WORLD, DOES LAST?

You want the answer? Human stories. Did you hear of the 50 year anniversary celebrations a couple weeks ago around the novel, “To Kill A Mockingbird”? It’s a truly great story that deals with fundamental aspects of humanity. It has the potential to live forever because of this. Humor and emotion. Tragedy and comedy. The Greeks figured this out long ago.

So, despite my terribly inept filmmaking efforts (hey, it was BEFORE I went to film school) in the making of “Salt of the Earth,” the simple fact is, the lobster fishermen (two brothers and their father) were so candid, so warm, so friendly, so funny, so crude, and in the end, so honest with the stories they told us that even with the bad camera work, the pathetic stock footage (we could only afford to purchase a few seconds of nice footage which we used in slo-motion, so slow the frames skip!), and my amateurish narration … the film is still every bit as enjoyable and moving today as it was nearly 20 years ago because of what the fishermen deliver.

Hey, everybody -- let's all go to Africa and shoot the same scene of a lion tackling a wildebeest that a zillion previous nature filmmakers have shot!

And that’s what makes for “shelf life” in the medium of film.

As nature filmmakers, year after year, keep shooting the same films of the same lions taking down wildebeests from the same herds in the Serengeti (a young British filmmaker complained to me once at the International Wildlife Film Festival about what he called “the perfect lion film” in reference to all the nature filmmakers who would rather reshoot this same sequence each year than go after any new stories) … as they keep churning out miles of footage of nature that fails to tell compelling stories with human elements … you begin to realize why there isn’t a list of the American Film Institute’s 100 Favorite Nature Films that everyone can agree on. They just don’t have the shelf life.

In the end, it’s not nature or science or sports or politics that people are really interested in. It’s people.