#47) The SHIFTING BASELINE of Environmental Journalism: Our Santa Barbara oil spill essay as a case in point?

June 21st, 2010

With major environmental outlets like The Grist in peril and Columbia University suspending their graduate program in environmental journalism because there are simply no jobs out there for environmental journalists, there’s widespread concern that the overall quality of environmental reporting will inevitably suffer. I think I may have seen the consequences of this already over the past three weeks as I looked into the parallels between the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 and the current Gulf oil spill. Being nothing more than an amateur journalist, I was ready to muscle my way into the pack of professionals I expected to encounter in Santa Barbara . Instead, I found that I had the place to myself.

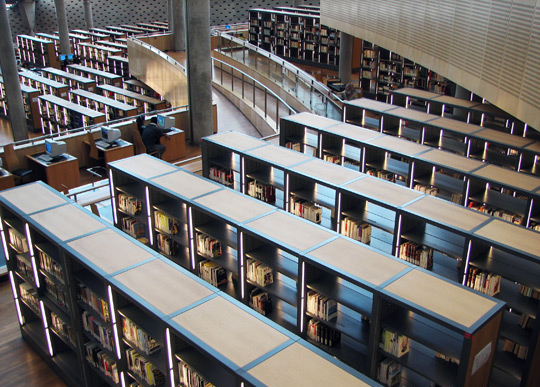

UCSB Special Collections: This is how many environmental journalists have visited it.

Eight years ago we began our Shifting Baselines Ocean Media Project with an OpEd I published in the LA Times about this “new” term “shifting baselines,” coined in 1995 by fisheries biologist Daniel Pauly and conveyed to me by coral reef ecologist Jeremy Jackson (by the way, don’t miss his recent TED Talk which is outstanding). The term refers to the failure to perceive change. I now want to offer up the suggestion that what we saw in the past three weeks here on The Benshi is perhaps a case study of the shifting baseline of environmental journalism, as follows.

PART ONE: The Decline in Environmental Journalism

For starters, there HAS been a change in the quality of environmental journalism. Not at the level of individuals — there are still plenty of brilliant environmental journalists across the country — but in the overall declining number of environmental journalists and the resources they have. This has been well documented such as here, here, and here.

PART TWO: The Worst Environmental Disaster in American History

It’s official, you can read it everywhere about the Gulf spill. Which means it’s also the biggest environmental story in the history of this country, and continues, after two months, to be the lead story on most news shows.

PART THREE: Where were the environmental journalists in Santa Barbara and Carpinteria?

Given the enormity of the story, you’d think a lot of journalists would seek to draw detailed comparisons between the Gulf spill and not the Exxon Valdez, which was a supertanker, but the 1969 Santa Barbara spill which was the same sort of blowout of an offshore oil well. And yet … where are the detailed comparisons? We offer up three data points that support what a lot of people have been suggesting — that environmental reporting ain’t what it used to be:

1) UCSB Special Collections, repository of the best collection of photos and news clippings of the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill — we visited it two weeks ago, they said no other journalists had been there

2) Robert Sollen, the first journalist to learn of the SB spill and author of, “An Ocean of Oil” — we interviewed him two weeks ago, no one else has bothered to talk with him other than one local TV news crew

3) Carpinteria Offshore Oil Drilling Initiative on June 8 – no major news media covered it other than a brief mention in the LA Times, despite being about the number one topic of the day, offshore drilling

PART FOUR: Why it matters that no journalists have pursued these resources

Because journalists have the potential to lead our society not just by shaping the headlines, but also by contextualizing the news. “Is it news?” is the first question a journalist considers, then, “Why does it matter to anyone?” To say that lots of wildlife in the Gulf are dying due to the spill is one message which will hold the public’s attention as long as the images are fresh. But to point out that this is a repetition of the same pattern, 40 years later, tells the public we have a long term problem that needs to be addressed. Journalists have the potential, if not the responsibility, to guide the public this way.

PART FIVE: The relevance of “shifting baselines”

There is a natural tendency towards the myopia of just focusing on “the here and now” in today’s information overloaded world. But that leads to a “putting out brush fires” mentality, and the inevitable risk that the size of the “brush fires” will grow over time — which is clearly the pattern when you compare the size of the Santa Barbara spill (200,000 gallons) to the Gulf spill (several MILLION gallons per week).

The purpose of calling attention to the problem of shifting baselines is to push the public to expand their perspectives beyond “the here and now.” The term arises from the fisheries world where fisherman might point to today’s abundance of a fish species being double what it was ten years ago, managing to make everyone feel good that the species is “rebounding.” The shifting baseline perspective forces you to look back 200 years and realize today’s populations may be only 2 percent of what once existed, which means that doubling it will still give you only 4 percent of the original numbers. The relevance of the term to the Gulf story is the idea that we assume that today’s environmental reporting is as good as it ever was. It’s not. Again, the declining numbers of environmental journalists tell the story.

PART SIX: Environmental reporting in a perfect ocean

In a perfect world major news outlets would have perhaps three environmental reporters — two that go to the Gulf and a third that digs deeper into the issue, visiting the previous, similar disasters to see what we can learn that is relevant. The idea that nobody visited the Santa Barbara resources is not a castigation of the poor over-worked environmental journalists of the moment, but rather an unnerving indicator of the consequences of such striped-down news media of today.

PART SEVEN: The predictions of EPIC 2014

In 2004 a biting seven minute Flash piece by Robin Sloan and Matt Thompson painted a picture of the near future of news media titled, “EPIC 2014.” The extraordinarily prescient essay (predicting the problems with news stripping services and the decline of the NY Times among other news outlets) concludes by saying in the future everyone will converge on EPIC, Evolving Personalized Information Construct, as the universal source of individualized news delivery. It finishes by saying:

“EPIC 2014 produces a custom content package for each reader using his choices — his consumption habits, his interests, his demographics, his social network to shape the product. A new generation of freelance editors has sprung up — people who sell their ability to connect, filter, and prioritize the contents of EPIC. We all subscribe to many editors. EPIC allows us to mix and match their choices however we like. At it’s best, edited for the most savvy readers, EPIC is a summary of the world, deeper, broader, and more nuanced than anything ever available before. But at it’s worst, and for too many, EPIC is merely a collection of trivia, much of it untrue, all of it narrow, shallow, and sensational. But EPIC is what we wanted. It is what we chose. And it’s commercial success pre-empted any discussions of media and democracy or journalistic ethics.”

When thousands of news stories are produced about the worst environmental disaster in American history, yet no one seeks out such obvious resources as the historical record of the most similar disaster, there is reason to believe the future has begun to arrive.