#30) MARK HARRIS, THREE TIME OSCAR WINNER FOR DOCUMENTARY: STORYTELLING IS AS MUCH A PART OF NON-FICTION AS FICTION

April 15th, 2010

Mark Jonathan Harris is one of the many amazing faculty to be found at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. He’s not just a great instructor and a warm and friendly professor. He’s also one of the most accomplished documentary filmmakers of today, having earned three Academy Awards. Similar to all my other interviews on The Benshi, I spoke to him with a fairly specific agenda, seeking his insights on aspects of filmmaking that are relevant to the world of science. On Monday I’ll give my analysis of both of this week’s interviews, pointing to some of the things Doug and Mark said, and talking further about the importance of storytelling to the mass communication of science.

Mark Harris: First news story as a journalist was about his own car

STORYTELLING, SCIENCE, AND NON-FICTION

RO: Science is, by definition, non-fiction. As a result, scientists tend to dislike the terms “story” and “storytelling,” believing they are meant only for the world of fiction. So let me begin by asking you this – does non-fiction documentary filmmaking involve storytelling?

MH: Yes, non-fiction documentary and dramatic films have more in common than the differences between them. They are both about telling stories.

RO: How would you go about pursuing the storytelling elements in making a non-fiction documentary?

MH: One of the differences between fiction and non-fiction is that in fiction you normally start off with a problem or a conflict. In documentary you start with a question that you want to explore.

RO: And what a coincidence – good science also begins with questions. So what was the question in your documentary feature, Into the Arms of Strangers?

MH: The question was, “What was it like for a child of ten or twelve to lose their parents, their home, go to a country where they knew no one, and didn’t speak the language – how did it shape their lives?”

Into the Arms of Strangers: Winner of the 2000 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film

RO: And how about for your documentary feature, The Long Way Home?

For that movie the question was, “How can people survive, and recover their lives after undergoing a catastrophe like the Holocaust? Is it possible to rebuild your life again?” Because at the end of the war, when people came to the concentration camps they saw all these emaciated, skeletal people, 70 or 80 pounds, and they thought, “These people will never be healed.” And so that was the question: “Can they heal, and what was the process of building a life after that?”

Like fiction films, documentaries have a beginning, a middle, and an end. And it is important that the question becomes more complicated. They follow the same basic rules of drama, “Get a kid up in a tree, throw stones at the kid, bring him down from the tree.” Problem, complication, resolution. In documentaries you take an issue, slowly complicate it and bring in other perspectives, so that at the end of the film you have a different perspective than you had at the beginning.

For me, when I come out of a movie and I look at the world freshly, from a new perspective, that’s a successful movie, and there are not many that do that.

Some are just entertaining – we go to movies to be entertained – but a movie that is really effective is one that makes you look at the world slightly differently – to see something that you haven’t seen before. It’s about discovery. You want to lead people through the process of discovery, you can’t just give it to them, they have to discover it for themselves. Everything important that I’ve learned in my life, I’ve had to discover. I don’t remember any important lesson I learned because someone told it to me. Even if people gave me good advice, I had to test it for myself to believe it. You know people are always telling you all sorts of shit. And you learn over time not to take everything at face value.

There’s a great saying I saw on a bumper sticker recently, “Don’t believe everything you think.”

The Long Way Home: Winner of the 1998 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film

RO: How much of making a film is intellectual versus instinctual – thinking things through versus just acting?

MH: Much of it is, despite all the rules, trial and error. But the more experience you get, basically, the stronger your instinct. Malcolm Gladwell’s the guy that says “10,000 hours” [the amount of time for something to become instinctual]. And at 10,000 hours you do have kind of an intuitive sense about what to do that you sometimes can’t articulate.

I sometimes joke that when I’m out making films and something’s not working, a scene is not working, I think, “Well, what would I tell my students here?” You know I have a few rules, and I go through the rules, and if it still doesn’t work, I think, “I’m in new territory. I’ve gotta find a new rule.”

MARK’S BACKGROUND

RO: Would you call yourself a historical filmmaker?

MH: When I started out, my early work was mainly cinéma vérité dealing with current events. Later on, starting with The Long Way Home, I began doing historical films. Most of what I’ve done in the last ten years have been historical films. I have two projects now – one is a historical film, the other’s a contemporary film. I’d like to get back to making contemporary films.

RO: Prior to making those films did you see yourself as a historian – do you have a background in history?

MH: I’m sort of a generalist. I started out as a journalist – I covered crime in Chicago from 5 in the afternoon to 2 in the morning. That was my introduction to professional life. Then I got into making documentary films in the sixties. I was a child of the sixties. I did a film about Cesar Chavez, I did a film about the Peace Corps, I did an early environmental film – “Redwoods” – a short film to help the Sierra Club to establish Redwoods National Park [which won an Oscar for Best Documentary Short Film in 1967]. That was one of the films that I’ve done that actually had a dramatic impact. I’d like to think it was helpful in establishing Redwoods National Park because it was shown to Congress. The Sierra Club used it as an organizing and advocacy tool.

RO: Did crime reporting teach you much about storytelling?

MH: It did. What was interesting – I was fresh out of Harvard. Most of the world I knew was straight out of books. The first six months I was a crime reporter I was carrying books with me – I was reading Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” (laughter) – asking myself, “Could this be an insight into the chaotic world I was experiencing every day?” The first story I covered — the first day on the beat, alone – Maxwell Street police station – I park my car out in front of the police station, I go in and ask the Desk Sergeant, “Anything going on” – “No,” he says, “it’s a slow day, kid.” I walked back outside – my car is stolen – this is my first story! “Reporter’s Car Stolen from Police Station.”

But you learn in journalism – because you have to do it quickly – you learn what’s important. Journalism starts with a kind of lead that tries to hook you. And the idea of hooking you into the story is something that’s continually relevant – how do we engage an audience? How do we get them curious? How do we get them interested? How do we get them to watch this thing?

CONNECTING WITH YOUR AUDIENCE

RO: What’s the answer to that?

MH: You try to intrigue them. There’s no single answer, but you try to pose a question that hooks them – that people want an answer to. It’s not exposition — it’s not explaining. You have to try to get them curious. The definition of storytelling I like best is, “Anticipation mixed with uncertainty.” That’s sort of like your “Arouse and fulfill” [cited in my book, but quoted from Tom Hollihan, who attributed it roughly to Kenneth Burke]. You get people to anticipate so they’re looking forward to how the story is going to progress, and they don’t know how it’s going to end – how it’s going to turn out.

So you pose a question – you raise an issue – you try to get people involved. The more the audience is involved in the movie, the more they learn from it. If you just present straight facts to them – if they’re not involved in the quest to answer this, or to come to some conclusion, they’re not going to learn anything.

RO: How do you get the audience involved?

MH: Through creating suspense – creating tension, conflict – asking questions the audience wants answers to. It’s as simple as, “Is she going to fall in love with him?” “Is she going to dump him?” On a simple, dramatic level – television writers are very good at that – to get you from commercial to commercial. So that even though you think, “This is dumb,” you watch the rest of it because you want to know how it turns out – is she going to get the criminal, is she going to win the case?

RO: Don’t you find that audiences connect with certain “voices” in a film?

MH: Yes, it’s very important, even in documentaries, that you cast the film well. For Into the Arms of Strangers we ended up with sixteen people, but we spent months interviewing, looking at tapes, and reading memoirs of about three hundred people until we finally came up with twenty one people that we wanted to interview, and we ended up after that with sixteen people in the film.

You need to have audiences care about your characters. Your mother in your film Flock of Dodos is someone whom we can all identify with. An every woman. That nice neighbor next door. Here’s this huge political and intellectual controversy going on, but one that seemingly has little to do with us, it’s very abstract, or something that doesn’t really factor into our lives, so why should we care about it? Your mother’s a way in to that. Casting can be critical.

RO: You know who’s amazing in Into the Arms of Strangers was that very elegant woman right at the very beginning because she’s the one that starts your story. Everyone’s telling these idyllic stories of everything is fine, and then she’s the first one that kind of changes the tone.

MH: In filmmaking you look for people whom the camera loves – people who have a kind of magnetism, people who come off as genuine. I just finished a film, which has been plagued by a lot of difficulties. One of the principal difficulties is that the main character is very difficult to like. He’s complicated, he’s fraudulent – audiences have a tough time with him. What he’s doing, his search, in this film is very interesting. But people are reluctant to go along with him, because they distrust him. So I think it’s important that the audience has some sense of identification, sympathy. I don’t think that every character has to be likeable, I just think they need to come across as authentic and genuine. When actors are not seen as genuine, those films have problems. An actor has to be believable.

RO: Have you read Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink?

MH: Yes.

RO: Because he talks about in there, those experiments where they showed just a ten second clip of a professor, ten seconds of video of that professor to the class, and the students instantly passed judgment on him. Do you feel that same way at times with casting for film, that it only takes a few seconds of a person on the screen for everyone to instantly have an opinion?

MH: Unfortunately I do. I like to believe that first impressions are not always the most accurate. Certainly in my life I have misjudged people. Sometimes you meet people and they have a prickly façade or other issues. But then you get beyond that and discover that they have more to offer. I would like to give people more than ten seconds.

Malcolm Gladwell guesses it takes about 10,000 hours to move something into the realm of true instinctive behavior

RO: [laughter]

MH: [laughter] You know I would like to think that I have more than ten seconds.

RO: [laughter] Right.

MH: But we do make those kinds of judgments. And in film I can give you an example. You know the film that Marty Scorsese did about Howard Hughes. Aviator. It’s like…Leo DiCaprio… I saw like the first minute, I’m like, “This is not Howard Hughes.” [laughter] And I’ve still got two more hours to go…I mean come on, how can I believe this? We all do that, there’s no question. Films are such a subjective experience. So casting is very important.

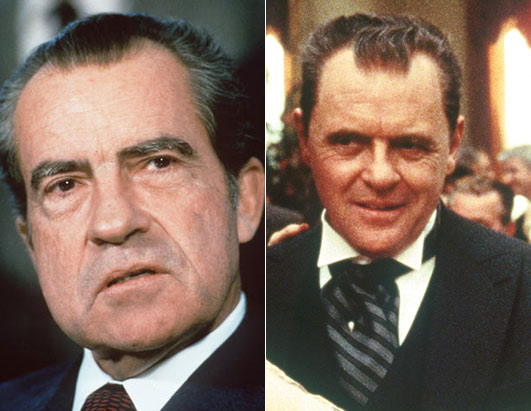

RO: Yeah I actually felt that way with Oliver Stone’s Nixon with Anthony Hopkins. It was just too much of a stretch.

MH: I know. And Oliver Stone is often like that. A friend of mine told me, “He’s not good with actors.” My friend has this great line about Wall Street. He says, “The acting is so bad, you don’t even believe Marty Sheen and Charlie Sheen are related.”

Pushing the Limits of Casting: Did you buy Anthony Hopkins as "Nixon"?

STORYTELLERS

RO: Let me ask you about “natural born storytellers”: Do you believe that some people are born better storytellers? And is storytelling ability part of the criteria for USC cinema school’s admission of students?

MH: If we knew how to look at students and pick talent, if we had a formula, it would be great, but I don’t think there is a formula. We’ve actually changed our admission criteria since you were here. We now ask applicants to write stories, an idea for a film. And also we’re asking for a five minute short video. Or there’s another opportunity, they can submit a series of photos and tell a story around them.

We look for people who can tell stories. We also look for people that have stories to tell. If you have stories, or you have ideas to tell, we think we can give you the tools to be a good storyteller, but developing visual and cinematic sensibilities – that’s harder.

As for good storytellers, let me give you an example. There are writers who are very good writers, but are not good at pitching their scripts in “the room” [in meetings with producers who might hire the writer]. In the old days, some of these writers used to hire someone to go into the room and pitch the script for them. The only problem was, the guys who were good storytellers, they were sensitive to the room – to the response of the room. And so if the tensions were flagging, they would say, “Oh, and there’s a car chase…” And start making things up that weren’t in the original idea of the writer they’re representing.

And so they’d come out and they’d sold the story, but it was not the story that the writer had been writing, and so then the original writer had to go out and write it.

USC School of Cinematic Arts: Pretty much the center of the universe when it comes to learning how to make movies

RO: That’s like athletic runners – some are sprinters, some are long distance.

MH: Yeah, but it’s also being sensitive to the audience’s reaction, and maybe these writers were sensitive in the room to where their listeners got bored or lost interest. I’ve always thought gifted storytellers have the ability to improvise and to change, or to ask in the interview the unexpected question, and catch people off-guard. I do think that people can be taught to do this. One way of learning to tell stories is reading stories and being responsive to them. And many scientists aren’t. I think some of the things you’re trying to do, like the improvisational thing, seem very inspired, you know, and seem to have an impact on people, an experiential impact.

RO: Do you think film is an effective “educational” medium?

MH: With both The Long Way Home and Into the Arms of Strangers, we did books because we had so much material. And it’s interesting to look at the difference between the books and the films. The books contain more facts, because they’re longer. When you look at a film, when you take a film script, it’s a fraction of what a book can say. So you’re obviously operating in a different way in a movie. Now what can a film do that a book can’t do? What a film can do is show you a person’s expression, it’s all the non-verbal behavior, it’s the emotion behind the facts, the tone of voice, the body language with which the facts are delivered.

People say that talking heads are not cinematic, well I think that talking heads can be cinematic, when they are emotional, when we are scrutinizing their faces to see if they are telling the truth. When they are giving information, facts, then they are not dramatic, and I never keep people on the screen when they’re delivering dry material, I always try to have visuals at that point.

But when people are thinking, when you can see them thinking – D.W. Griffiths famously said that the camera can photograph thought – well then that’s a different story. There’s a wonderful moment in a film that John Else did about Robert Oppenheimer called The Day After Trinity. John is interviewing Robert’s brother Frank Oppenheimer and asking about his reaction to the bombing of Hiroshima. And it’s such a difficult question for him. The camera is stationary, and Oppenheimer is moving in and out of the frame of the camera – out of the scrutiny of history – and you really see his anguish at the question. He just doesn’t want to answer it. He doesn’t want to be held accountable for that. I feel he’s moving in and out of the frame because he’s trying to evade the judgment of history. And I think the interview is very dramatic because of that.

If you’d just written that on a page, you wouldn’t get that. And that’s what film can do that a book just can’t do. So you try to take advantage of what the medium does well, and you use its emotional power to convey your message…

The Day After Trinity: Frank Oppenheimer speaks volumes with his body language

RO: So you think film has a hard time with just facts.

MH: A lot of facts are expositional, and that’s one of the major challenges – it’s about disguising exposition because it tends to be difficult in a film. There’s an old adage that, “It’s easier to make people cry in a film than it is to make them think.” Certainly you try to link the two, but it’s difficult because film is a visual medium, an emotional medium. If you are trying to make people think, essays are better because people can go back and forth, they can look, they can ponder the arguments. But film is action in time, it is a time based medium.

RO: Well, then. In terms of your two major films on the Holocaust, were you going more for crying rather than thinking?

MH: I wanted to do both, to give people an emotional experience that would provoke them to think. Part of this was presenting a variety of experiences, seeing the Kindertransport from many different perspectives. But no, this is not like a Godard-ian film, which is very intellectual, paradoxical. I wanted people to experience what it was like for a child to lose their parents and home, which is the greatest trauma a child can have in their life. But I also was casting it with a lot of different people and a lot of different viewpoints, so you can see how complex of an experience this was. I’m making documentaries so yes, they are definitely films about ideas. But I also believe you learn through experience, and that’s what sticks.

RO: So you feel there’s a limit to how much information can be conveyed?

MH: Yes. Because film is a time-based-medium you have to impart your ideas slowly, kind of…one…idea…at a time. I think you can deal with complex ideas, but because you can’t go back, you have to make sure the audience is with you every step of the way. So in my documentary course, I’m famous for saying, “It has to be chimp simple.”

I know that sounds funny, but there’s a truth to it. What’s been said about American Dramaturgy, what we’ve had to contribute to storytelling, is the art of the striptease. You know, in striptease you take off the glove…one…finger…at a time. You don’t just take off all the clothes. You titillate…you excite the audience, but you do it slowly…one piece of clothing, one item at a time. And that’s the central way you try to put ideas in films.

“AN INCONVENIENT TRUTH”

RO: What was your take on An Inconvenient Truth?

MH: I thought it was obviously incredibly successful – it got Al Gore the Nobel Prize and brought the issue to the attention of the world. And it did so far more effectively than Al Gore did in terms of his slide show presentation because it had a larger audience, but also because it humanized Al Gore. He had lost the presidential election because he seemed wonky. People couldn’t relate to him because of all the negative qualities they attributed to him. Davis Guggenheim [the director] was very shrewd in making Al Gore sympathetic by seeing him, the former presidential candidate, carrying his luggage through the airport – schlepping around, from city to city – the lone man on his journey to educate the world. It made him seem sympathetic, which was why it was effective.

But I actually have one issue with the film, which is that Al Gore – and it’s a problem of the entire environmental movement – is saying that it’s our moral duty to do this. Instead of appealing to people’s self-interest and saying we’re all in this together, it’s a matter of survival – he’s saying it’s a moral issue – so that, “I’m moral because I want to do it, and if you don’t want to do it, then you’re immoral.”

I think that sets up a divide that we’re still dealing with – the environmentalists as the do-gooders, holier than thou. I think it’s a matter of survival of the planet for all of us to participate in this. So that’s why I think the moral argument isn’t the most effective way to convert people who don’t believe in global warming.

RO: Do you think the movie told a good story?

MH: It did tell a good story.

RO: A well structured, three-act story?

MH: Um…

RO: What was the source of tension or suspense?

MH: It’s the crisis of the planet. Is the planet going to fall apart? Is the planet doomed? He’s trying to warn us. Here’s this guy on his quest to tell us the planet is doomed. Are we gonna get the message? I thought that was it.

RO: Do you think it’s a film that people want to watch a second or third time?

MH: I haven’t.

SCIENCE FILMMAKING

RO: And one final question. Have you ever thought of doing any films related to the world of science?

MH: Actually, I have a really interesting project now that does have some science in it. It’s called Dinner Party with History, and it’s based on Steve Allen’s old Meeting of Minds. It will focus on historical issues, leadership, Lincoln, Malcolm X, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, a whole world of ideas, but the pilot project, which Kirk Ellis has written the script for, is called Evolution and its Discontents and it stars Aristotle, St. Augustine, Darwin, and Barbara McClintock having a dinner party.

The idea is all these people from different eras, they come together to talk about evolution. We’re doing this for a general audience, we have to let people know who they are, and have a conversation between them that carries the audience along and that has enough humor in it because these, as you know, are very difficult ideas. And just to give you a taste – at one point when they’re all together Barbara McClintock says, “I have a word that you’ve all never heard before – the word is, “Chromosome.” You can imagine where the conversation can go from there!