#389) A Simpler Take on Lying: Narrative Dynamics

May 5th, 2015

There’s a popular and fun TED ED animated video about applying “communications theory” to lying that came out last fall which is nice, BUT … it’s still more complicated than necessary. It attempts to identify several characteristics of liars, but there’s a simpler principle underlying most of what is said, which is the fundamental rule of, “the power of storytelling rests in the specifics.” Bottom line: Dude, most of this stuff just ain’t that complicated.

LIAR, LIAR, WORDS ON FIRE

Last fall Noah Zandan, who is big on “quantified communication” posted a fun TED ED video about ways to spot liars using “communications theory.” He opens the video with a simple ABT about how lots of ways have been developed over the ages to detecting lying AND they all work to some extent BUT ultimately they can all be fooled, THEREFORE we need a different means to analyze the language of a liar. From there he points to what is called linguistic text analysis.

Which is nice, BUT … I’m going offer up an even simpler way to look at this, which is to examine the underlying narrative dynamics.

THE CLEAR TRUTH ABOUT OBFUSCATION

What he presents are four different shapes of the language used by liars. In the video he gives detailed explanations of each and offers up examples, especially from famous politicians who got caught lying (no shortage of material there). Here’s what he concludes — four language patterns common among liars.

1 MINIMAL SELF-REFERENCE – “liars reference themselves less when making deceptive statements” “often using the third person to distance and dissociate themselves from their lie.” What this means is putting the focus on someone or something else, leaving yourself more vague.

2 NEGATIVE LANGUAGE – “liars tend to be more negative” “for example they might say my stupid cell phone died, I hate that thing.” This means they add on extra, conflict-rich wording as a means of distraction.

3 SIMPLE EXPLANATION – “liars typically explain events in simple terms” “As a U.S. President once famously insisted, ‘I did not have sexual relations with that woman.’” This means in addressing the material they need to lie about, they resort to vagueness.

4 CONVOLUTED PHRASING – “liars tend to use longer and more convoluted sentence structure, inserting unnecessary words and irrelevant but factual-sounding details to pad the lie.” They achieve vagueness through narrative confusion.

The overall pattern is: DISTRACTIONS: clarity good THE LIE: clarity bad

THE NARRATIVE RE-INTERPRETATION

I don’t know exactly what “linguistic analysis” is but it sounds more convoluted itself than what is needed to grasp the basic dynamic of what’s going on. The core principle at work is basic storytelling, for which one of the most simple and universal principles is that, “the power of storytelling rests in the specifics.”

Take a look at these four patterns described and you can see at their core, the main variable at work is simply specific versus general communication. If the liar is wanting to distract, then specifics provide the power. If the liar is wanting to be vague, then leaving out specifics is the answer.

1 MINIMAL SELF-REFERENCE – liars paint a SPECIFIC picture of something else, leaving themselves more general and vague

2 NEGATIVE LANGUAGE – conflict-rich SPECIFICS distract from the truth

3 SIMPLE EXPLANATION – the liar is covered up by not being SPECIFIC (remaining general and vague)

4 CONVOLUTED PHRASING – the lie is covered up by presenting an overly SPECIFIC narrative

He also goes on to apply “linguistic analysis” to the lies of Lance Armstrong and John Edwards. But in both cases, it’s the same simple pattern. When the dude is lying, the narrative is weak through over-complication or being non-specific. When he wants to be honest he is specific. Same, same.

He ends by saying how you can use this information in your daily life. He offers up the four categorizations, but I’d make it simpler, which is more useful — just develop a sensitivity to “the power of specifics” in storytelling.

FOREVER STORYTELLING ANIMALS

As Jonathan Gotschall said with the title of his 2013 book, we are, “Storytelling Animals.” This is the core premise of my upcoming book, “Houston, We Have A Narrative,” which will come out in September but is now posted on Amazon. What the book is about is that we have been recording stories for at least 4,000 years, but recorded science only goes back a few hundred years. Which begs the question of which means of communication would you expect to be more dominant?

The idea of “linguistic analysis” sounds cool, but in the end, the simplest and most powerful of all dynamics for understanding communication is simply narrative, for which there are just a few very simple rules of thumb that explain so much. The power of specifics is perhaps the most all-encompassing of all. The deeper you absorb it, the more you see how much of what goes on in our world is driven by it.

And p.s. — beware of communications folks looking to over-complicate the world. When I finished film school at USC I did a 20 minute video called, “Talking Science” where I interviewed faculty from both the Cinema School and the Annenberg School of Communication. That’s where I first saw this pattern, clear as day. The communications folks could theorize about how to communicate. The film folks knew how to actually communicate.

388) Skillful Messaging from Marco Rubio

April 14th, 2015

In my upcoming book I present something I have labeled as “The Dobzhansky Template” for finding the core theme or message of a narrative. Marco Rubio gave a speech yesterday that felt almost like he had used the template. It was a model of clear messaging.

HOW TO MESSAGE EFFECTIVELY IN A SPEECH by Marco Rubio

MESSAGING 101

I’m not a fan of Marco Rubio (the dude’s a climate skeptic for starters), but he showed the kind of aggressive messaging that the right wing is so adept at in a speech yesterday, labeling his opponent, Hillary Clinton, with exactly that word — “yesterday.” Here’s what he said.

RUBIO: Just yesterday, a leader from yesterday, began a campaign for president by promising to take us back to yesterday.

Skillfully done. And kinda funny, too.

THE DOBZHANSKY TEMPLATE

In our Connection Storymaker Workshop of the past 5 years we developed the idea of a template for finding “the one word” at the core of your narrative using the famous quote from geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky (“Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”).

The idea is the search for “the one thing” that captures the bulk of the narrative. Here’s the sentence as a template:

Nothing in _____ makes sense except in the light of _____ .

And here’s the template as Rubio would have used it.

Nothing in HILLARY CLINTON’S CAMPAIGN makes sense except in the light of YESTERDAY.

The object of messaging is that once you figure out that one thing — you hit the note over and over, from a variety of angles. As Rubio did in a single sentence. I’m not sure about the rest of his speech, but he could easily have continued hitting that message in multiple ways — always coming back to the bottom line — that his opponent is out of touch with today.

It’s a very simple and fairly harsh label to put on her, but that’s how it’s done by the big boys — creating the frame around their opponent before the opponent can create their own frame. Whether it sticks remains to be seen, but for now, it was a model effort for how a challenger takes on a superior opponent. It’s also a cue for her to swing back, which she hopefully does with equal skill.

#387) The Story Circle Prototypes

April 13th, 2015

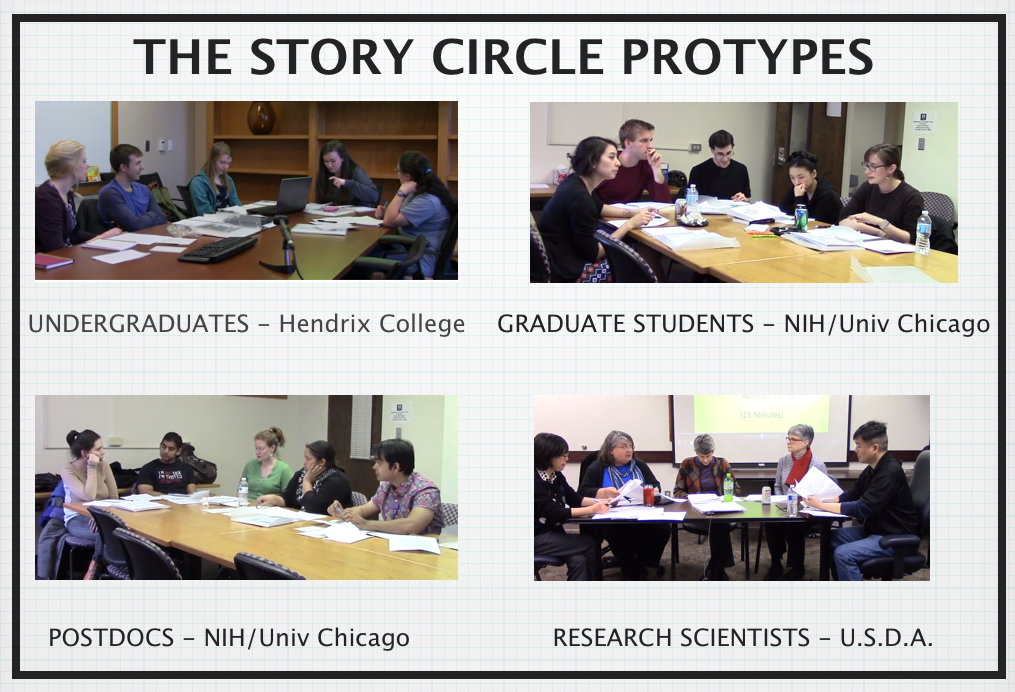

One is complete, the other three will finish by the end of next month. Ten hours and you’ll never view text the same.

ABSORBING NARRATIVE STRUCTURE AT THE GUT LEVEL. The four prototypes that started in late January.

THE CURE TO BOREDOM AND CONFUSION

It’s very simple. At the core of it everything is the ABT — the simple structuring device that tracks back to Aristotle. It’s the narrative ideal. Everything else is either a tiny bit more boring or a tiny bit more confusing.

It’s five people doing 10 one hour sessions where they first, analyze the narrative structure of abstracts, then work on their own stories using the narrative tools developed in our Connection Storymaker Workshop.

The specifics are laid out in my new book, “Houston, We Have A Narrative: Why Science Needs Story,” coming in September. All of the sessions have been recorded. We are about to begin analyzing the videos, producing a novel data set on how people improve their communication skills.

Story Circles is the solution to the problem I laid out in the third chapter of my first book. The chapter was titled, “Don’t Be Such A Poor Storyteller.” It puts you on the path to solving that problem.

Big thanks to George Harper (Hendrix College), Mike Strauss (USDA), Alan Thomas (NIH/Univ of Chicago) and all the wonderful participants.

#386) THE NEW BOOK: Table of Contents

April 7th, 2015

#385) STORY CIRCLES (NARRATIVE FITNESS TRAINING): Three Prototype Circles Now In Progress

March 13th, 2015

Just got back from Chicago where Story Circles co-producer Jayde Lovell and I launched the postdoc-level prototype of Story Circles. This one is being sponsored by the NIH/University of Chicago My C.H.O.I.C.E. program. I’ll return in three weeks to launch the grad student prototype. In the meanwhile, next week will be the 10th and concluding session of the undergrad prototype at Hendrix College where five brave and intrepid students, in addition to enjoying it, are now changed for life. Never again will they bore or confuse anyone. Hopefully. They also had a lot of fun.

OPERATION STORY CIRCLE: Five people, one hour a week, ten sessions. That’s what each circle consists of. We liken it to fitness training. We give you the narrative tools on the first day, you just do weekly one hour workouts consisting of analyzing research abstracts with the tools, then work on your own stories with them. Almost no homework. Pretty much the same as going to the gym, just a different set of muscles you’re working out.

THERE IS A CURE TO BOREDOM AND CONFUSION

COMPASSIONATE COMMENTATOR: There’s no need to suffer narrative deficiency alone any more. A cure is here. It’s called Story Circles. It’s fun, it’s painless and it works. Ask your doctor about Story Circles today.

That’s going to be the tagline eventually for our TV commercial for Story Circles when that day arrives. For now, it’s time to start spreading the word — Story Circles works.

With Story Circles (sounding like an infomercial again, sorry) you’ll never look at content the same way.

It’s true. How can it not be true. There simply aren’t any tools for simple structural analysis of narrative. Now there are.

We can see it in the undergrad prototype group at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas. Two months their analysis of content was little more than, “It’s not very well written — kind of clunky, doesn’t flow, didn’t grab me, too wordy.” Inarticulate, mostly just gut level analysis.

Now they have specific vocabulary to analyze structure analytically. They have a whole page of terms and templates, most of which can be found in my last book, “Connection,” all of which will be found in my new book in September.

Big things lie ahead for Story Circles. For now we need to finish the prototypes and analyze them properly (everything is being videoed). This will give a clear picture of how it works and what can be expected. Then we’ll be ready to release it widely.

I’m in Chicago next week, speaking at University of Chicago, launching our third Story Circle prototype with a group of their NIH postdocs, and meeting with the good people at University of Chicago Press who just locked this in as the cover artwork for the new book.

TIME FOR A CHANGE. A lot of thought has gone into that subtitle — “Why Science Needs Story.” The world has changed. We are now driven by communication dynamics, which in turn are driven by 4,000 years of storytelling. It’s time for science to catch up with this. I’m not saying scientists need to tell stories, only that they all need to understand how it works better.

#383) Improv: A Tool to Avert “Negation Nose Dives”

February 19th, 2015

Ever been part of a discussion where everything suddenly turns negative as the group rips up every good idea, plowing the whole thing into the ground? I’ve seen a few. Related to this, I heard a wonderful comment last week from a scientist about the impact of our improv training on their organization.

HAVE YOU EVER … been part of a discussion that turned negative and ended up like this? Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a way to pull out of such a negation nose dive?

Happens every day, in conference rooms around the world. It’s not just a science thing — but the negation/falsification process of science can make it worse.

Sometimes it feels really good as you watch a flimsy idea get taken to pieces through tough, incisive questioning that has at the core of it the premise that everything presented is wrong until shown to be otherwise. It’s what science is based upon — a process of falsification — testing ideas to see if they can be falsified until you finally have subjected them to so much rigor and they haven’t failed that you can conclude you have something robust. It’s great when it works that way.

But it comes with a potential down side, which is the tailspin of unrestrained negation, obliterating everything that might have been salvaged as worthwhile.

SOLUTION: CHANGING THE COURSE OF DISCUSSIONS

A little over two years ago we ran our Connection Storymaker Workshop with the folks at National Park Service headquarters in Ft. Collins, Colorado. We had two groups of about twenty people each. It felt like a successful experience, but I never believe anything I do really works until someone gives me some proof (me to self: “Don’t be SUCH a scientist!!!”). Which is what happened last week.

I had a long phone call with one of our hosts. He said, “You wouldn’t believe how many times in discussions, since that training, we have brought up the basic, ‘Yes, and …’ approach you taught us in the workshop. There have been multiple instances when everyone is headed in a negative direction, then someone says, “Let’s remember the ‘Yes, and …’ thing,'” and the discussion reverses almost immediately.”

That warmed my heart sooo much. It had never dawned on me — that application of improv. We always present it as a tool for enhancing creativity, making you more human and alive, getting you out of your head … but I’ve never thought to talk about it as an emergency maneuver for a negation nose dive.

Yes, and … I think I’ll be including that attribute of improv in the future when I talk about it. I can’t say enough good things about the training, and Brian Palermo (who will be doing improv next week at the ASLO meeting in Spain).

#382) New Brian Palermo Video on Improv and his ASLO Workshop in Spain

February 10th, 2015

#381) Climate Boredom: Muller vs. Mozart

February 2nd, 2015

After my panel last week with Derek Muller at the North American Carbon Program meeting in DC a few people noted how Derek and his video on climate boredom point to the subject of climate as inherently boring whereas I point to the communicators themselves as doing an inadequate job. Let’s take a closer look at this divide.

IS CLIMATE INHERENTLY BORING? I have a feeling this delegate from Iran to the recent climate change conference in Peru would say so.

DEREK: IT’S THE MATERIAL

Derek Muller produces awesome videos on his Youtube Channel Veritasium. In our panel he showed his video, “Climate Change is Boring.” Towards the end of the video he says, “The real reason I find climate change boring is because we know what the problem is — the science is well established and the solutions are fairly obvious, and yet action is not being taken.”

I love the video, but I don’t agree with his premise that climate is somehow intrinsically boring and thus a hopelessly difficult subject to communicate. I think there’s plenty of reason for hope that some day someone will produce a film about global warming that involves such excellent storytelling that generations will want to watch and rewatch it as much as “The Wizard of Oz.” Here’s how that could happen.

ME: IT’S THE MOZART (A HUGELY CREATIVE EYE IS NEEDED)

I love innovation and creativity. I pretty much live for it. And I know it requires less literal thinking.

A great case study of the power of innovation and creativity is what happened with the life story of Mozart in the movies. It’s a good parable for this climate boredom problem.

Similar to the subject of climate, for decades in Hollywood the subject of Mozart was seen as too boring to be the focus of an entire movie — there just wasn’t a good story. People figured he was such a genius, there must be a good story. But there wasn’t. There was only the “and, and, and” elements of a good resume: Mozart was a child prodigy AND he was a teen prodigy AND in his twenties he continued to be a genius AND by the time of his death at just 35 he was … still pretty much of a genius.

You could make a movie of all that, and the Mozart fans would probably love it as they got to hear their favorite music and coo over how amazing he was. But that’s not great storytelling. That’s a journey from Point A to Point A. And as a result, no one was able to make a memorable movie about Mozart. All the way up until 1984.

THE NON-LITERAL ROAD LESS TRAVELED

Finally a brilliant playwright named Peter Shaffer cracked the nut. Instead of telling the one dimensional story of Mozart the genius, he took a less literal, more creative approach to the material. He discovered this other character — Salieri — a man whose life story was indeed an interesting journey. Salieri began life thinking he was a peer to Mozart, but by the end of his life was forced to accept that he was a mere mortal, not made of the same stock as Mozart the genius, and thus ended his life a bitter and jealous man, filled with the sort of human frailties that interest audiences.

The play was turned into the movie “Amadeus,” which is #53 on the AFI List of 100 Greatest Movies. It’s one of my all-time favorite movies. And it should be an inspiration to people wanting to communicate about climate in a way that will stick with people many years later.

The fact is, it would have been easy in 1980 to say, “Face it, Mozart is boring, you’ll never manage to interest people in him.” But after the movie came out no one would have called Mozart boring.

THE SCIENCE COMMUNICATION HIPPOCRATIC OATH: “First, Do No Boredom”

I have said before, science communicators should almost take a sort of Hippocratic Oath swearing that there is no such thing as a boring subject, only inadequate communicators.

It’s the truth. Just watch HBO’s Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel. They manage to take the most trivial and unknown of sports events and tell fascinating stories set in those worlds because they have the ability to spot an interesting story when it comes along.

Perhaps some day the climate communication people, with all their good intentions, will develop this ability. But for now all they seem capable of is telling endless preachy “and, and, and” pieces that simply make things worse. And make it easy to feel like the subject of climate is inherently boring.

Some day someone will crack the climate communication nut as well as Peter Shaffer did for Mozart. And it will be great. And transformative as overnight people suddenly think climate is interesting. I will happen eventually, I’m sure of it. But until then, all I see is a dire shortage of creativity.

And if you want to see the consequences of the one dimensional, “and, and, and” approach all you have to do is watch the recent movie, “Unbroken.” The book was tremendous, but what Angelina Jolie did was sad and inept. She made a movie that was exactly the sort of one dimensional “and, and, and” piece that I’m bemoaning here. Her movie ended up being a series of episodes of Louis Zamperini overcoming one challenge after another. No arc, no complexity, no inner journey. Just a resume of accomplishments.

The Motion Picture Academy actually regained some of my respect by announcing only 8 nominations for the potential 10 Best Picture slots this year. Universal Studios spent all last year saying “Unbroken” would be a guaranteed nominee. Not only did it not get a nod, it’s doubly painful because it wasn’t like there too many nominees this year. There weren’t. The Academy basically said, “We’ve got space for your movie, but it’s just not very good.”

“Unbroken” ended up with around 50% on Rotten Tomatoes, but even most of the favorable reviews really weren’t that favorable. Angelina has learned the hard way there is more to storytelling than just listing facts. Telling good stories is hard, but absolutely essential to break out of the core demographic of followers.

#380) Communicating Carbon In A Bored World

January 29th, 2015

I’m willing to bet it’s the very best element-based meeting in the cosmos. I’m talking about the North American Carbon Meeting, where I took part in a panel discussion yesterday with two excellent communicators — video superstar Derek Muller from Australia and Banana/Coal communicator Peter Griffith of NASA. You can talk about nitrogen, phosphorus, argon, strontium, ruthenium, samarium, hassium or meiternium — none of them have a meeting that compares with this carbon meeting. However, there is an “element of truth” to Derek’s Youtube video channel Veritasium being the best in online science videomaking.

TWO NICE GUYS AND A GROUCH. Derek Muller (left) won my immediate respect by saying climate change is boring. In fact he has this excellent video explaining his thoughts on it. Peter Griffith of NASA also has a great short video about the carbonic difference between a banana and coal.

TWO NICE GUYS AND A GROUCH. Derek Muller (left) won my immediate respect by saying climate change is boring. In fact he has this excellent video explaining his thoughts on it. Peter Griffith of NASA also has a great short video about the carbonic difference between a banana and coal.

AND THAT’S WHEN THE CARBON DIOXIDE CONCENTRATION REACHED 400 PARTS PER MILLION …

Global warming is bo-ho-horing. Andy Revkin quoted me on this in 2010 in his NY Times Dot Earth blog, then the good folks at Der Speigel a couple years ago had me expound in this in their magazine.

So it was a joy to meet Youtube video legend Derek Muller from Australia (his Veritasium channel on Youtube has over 2 million subscribers) who has made entire videos addressing the difficulty of communicating this challenging yet important issue. We were on a panel at the annual meeting of the North American Carbon Program (NAACP) in Washington D.C., put together by the meeting organizer, my old buddy Peter Griffith (we go back to the Carboniferous Period where we met as undergrads at Duke Marine Lab).

Peter is one of the “thousand points of light” in the science world whose support gives me cause for optimism in the relentless battle against the science establishment (who have never supported anything I’ve ever done in science communication). He and I got reacquainted in 2009 when I spoke at NASA. We hadn’t crossed paths in decades.

IS THAT A BANANA IN YOUR PANTS OR A LUMP OF COAL?

Peter is one of those folks who is a natural born communicator, and not surprisingly has taken a great interest in my two books. In fact, my pushing and proding helped spur him to make this excellent video of his simple comparison of a banana and coal to convey the difference between new carbon versus old.

A lot of the major essays I have posted here over the past five years originate with Peter sending me an email with a recent thought or article. He is proof that you can be both an excellent (carbon) researcher and excellent (carbon) communicator.

Together the three of us on the panel opinionated on the difficult yet important task of communicating about climate change in a world that is driven not by facts but by narrative dynamics (which of course is the topic of my new book coming in September). People are always asking me who I think does a good job of communicating science …

Simple answer: Derek Muller. And not just a good job — his videos really are superb — both entertaining yet with deeper dimensions, looking at the basic science of how we reason and why some science topics are so elusive.

I hate to say this about all the well-intentioned feature documentary filmmakers out there, but Derek is the face of the future of filmmaking. The masses are losing their interest in the 90 minute format. All you have to do is visit Culver City in Los Angeles and look at the sprawling Youtube facilities to see where the future lies. Derek is on the cutting edge of this new medium of mass communication, and makes you realize the future is bright.